Since April 2021, police abolitionists and environmentalists have been engaged in a furious struggle to prevent the destruction of a precious stretch of forest in Atlanta, Georgia, where the government aims to build a police training compound and facilitate the construction of a giant soundstage for the film industry. In the following analysis, participants in the movement chronicle a year of action, tracing the movement’s victories and setbacks and exploring the strategies that inform it. This campaign represents a crucial effort to chart new paths forward in the wake of the George Floyd Rebellion, linking the defense of the land that sustains us with the struggle against police.

This week, activists in Atlanta announced a new website, stopreevesyoung.com, and a nationwide day of action on May 1 aimed at pressuring the construction firm hired to destroy the forest. On April 22-23, Muscogee community members and forest defenders will gather in the forest for discussions, skill shares, and a press conference. A third week of action is scheduled for May 8 through 15.

If you are looking for ways to keep the earth inhabitable and put a stop to police oppression, this could be your chance.

Read on to learn the lessons of a year of forest defense.

“When a tree is growing, it’s tender and pliant. But when it’s dry and hard, it dies. Hardness and strength are death’s companions. Pliancy and weakness are expressions of the freshness of being. Because what has hardened will never win.”

-Stalker, Andrei Tarkovsky

The forest.

Defending the Forest in the City

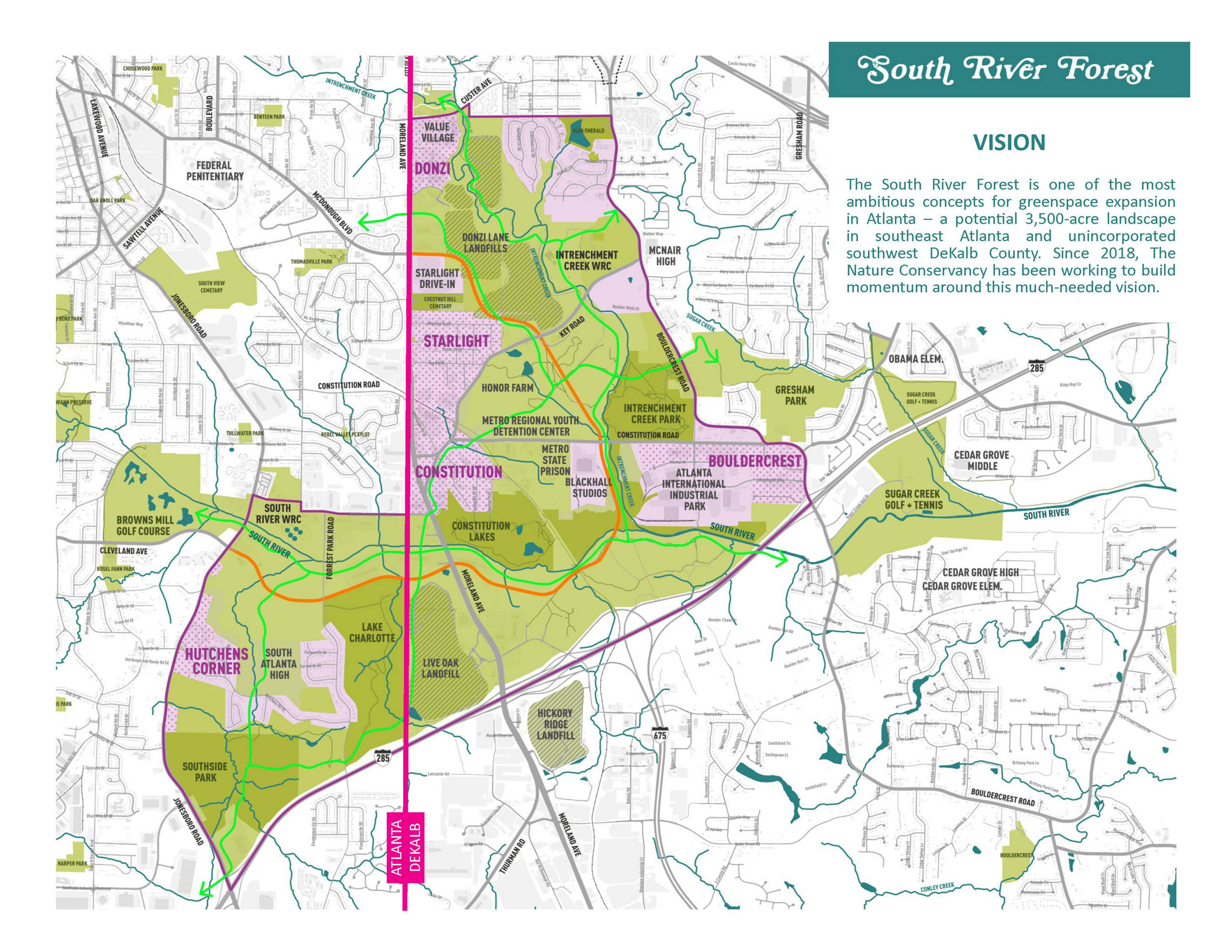

Atlanta is a city in a forest, with the most tree coverage of any urban center in America. The South River Forest constitutes the largest continuous section of this forest; it functions as the “lungs” of the city, trapping carbon emissions and runoff in its marshy lands and dense tree canopy. The South River Forest connects other forested areas across the entire southern half of the city and up the east side into Decatur. It is not uncommon to see deer running or playing in the woods—a breathtaking experience, especially in a city. Away from surveillance cameras and strip malls, teenagers go on dates, enthusiasts ride mountain bikes, and elderly people walk their dogs.

This is where the governments of Atlanta and Dekalb County and the Atlanta Police Foundation are attempting to build a police training compound. Next door, in Intrenchment Creek Park, a scandalous land-swap deal will give public lands to Blackhall Studios, who hopes to expand their nearby soundstage complex into the biggest such facility on earth. This forest forms an essential link in the urban wildlife corridor, which these developments will destroy. If the developments go forward, the entire metropolitan area, which is currently insulated from the worst consequences of ongoing climate collapse, will experience worse floods, higher temperatures, and smog-filled afternoons just as the world enters a century of climate crises and ecological collapse.

If the developments are completed, everything surrounding and east of Starlight and Constitution will be destroyed.

The area where the Police Foundation hopes to build their training compound is also the site of the Old Atlanta Prison Farm. In the 19th century, slaves worked this land after it was taken from the Muscogee (Creek) people, who call the area Weelaunee. During Reconstruction, the land briefly operated as a dairy works; afterwards, it was turned into a prison camp where prisoners were forced to till fields and rear animals in dehumanizing conditions. Some were even lynched. Paving this land over with new carceral infrastructure perpetuates a historical continuum of dispossession and abuse.

Opponents of these plans regard the police training facility—dubbed “Cop City”—and the Blackhall development as interrelated aspects of the same repressive restructuring of Atlanta. In short, the Blackhall development will exacerbate economic disparities and ecological collapse, while Cop City will equip the police to preserve them.

The movement opposing these developments, mobilizing around the watchwords Defend the Forest and Stop Cop City, has passed through several phases of experimentation, using a wide array of tactics and strategies to keep pace with the course of events. It represents an important effort to revitalize eco-defense and police abolition strategies in the wake of the George Floyd Rebellion.

Old Atlanta Prison Farm. An old truck is repurposed.

Background

To understand the movement, it’s necessary to back up a bit.

The Atlanta Way

“Historians say The Atlanta Way has its roots in Black and white business leaders meeting behind closed doors to negotiate incremental advances in racial issues to avoid public protests and preserve the city’s business-friendly image.

In the 1960s, it helped the city overcome the turmoil of desegregation and become a national leader in the Civil Rights Movement. Atlanta emerged as the economic capital of the Southeast. That reputation has endured for decades, thanks to the many champions of The Atlanta Way in business and government.”

–“The Atlanta Way is an Ideal Never Fully Realized,” Atlanta Business Chronicle

The “Atlanta Way,” as it is known locally, is a model of social management that goes back to the early 1960s. During the re-emergence of Black resistance movements in the Deep South after the Second World War, business leaders, landlords, government officials, and industrial magnates established a cross-caste alliance for the express purpose of forestalling racial justice movements in the city. They hoped that by increasing cooperation between the white corporate power structure and the Black business class, they could pre-empt the demands of the exploited Black masses without significantly altering the post-war capitalist economy, which brought unprecedented power to the ruling class in the United States following the destruction of European industry. Developed in the Jim Crow period and its immediate aftermath, the Atlanta Way subordinated public policy to the personal relationships and back-door dealings of the rich, a trend that continues to this day.

The basic structure of pre-emptive counterinsurgency reflected in the Atlanta Way strategy dictates that Black people hold political office and fill roles in administration, policing, and the justice industry. In return, those who hold these positions are expected to impose repressive policies, budget cuts, and mass privatization on the region’s Black and poor majority. Many Georgia liberals believe that assuring progress on racial inequality means creating financial and business incentives for developers, universities, construction companies, industries, and real estate investors. Nepotistic patronage systems—similar to what is known as clientelism in some parts of the world—are supposed to foster a thriving Black middle class.

Yet Black residents of Atlanta are still overrepresented in the city’s jails, unemployment statisics, food lines, and probation offices. All of the large public housing developments in the city have been closed down, all of the large shelters for the houseless have been shuttered, and historically Black neighborhoods face an unprecedented influx of non-Black tenants displaced from other cities and neighborhoods by the rising costs of living around the world.

The Atlanta Way connects our time to the Jim Crow era. Without it, Atlanta would not be a major destination for profiteers and businessmen. By organizing city affairs around private agreements between politicians and capitalists, by coordinating investments and commerce according to the principles of privatization and corporate incentives, the architects of this system have smuggled Reaganite neoliberal policies into institutional leftism. In framing this as “anti-racist,” political elites deprive poor people of a necessary tool for fighting against immiseration. Indeed, the Atlanta Way could make it appear that anti-racism is simply a creative way to package the plundering of resources by politicians and their colleagues in the business and non-profit sectors.

Today, Atlanta has become the most unequal city in the continental US, and the Atlanta Way is beginning to break apart. Direct resistance to police brutality and racism also has a long, militant, history here, and it is clear that the years ahead will create a hostile environment for the ruling cliques. This is the context in which we can anticipate a new wave of resistance to the Atlanta Way from above. International investors and increasingly white, wealthy enclaves have no long-term investment in the urban core; they use the city as a space for profiteering because of its low taxes and relatively affordable land. Resistance will also come from below: from renters, workers, students, prisoners, young people, and residents facing displacement and erasure. The discourses of the past century will no longer serve to reconcile these two camps. The city government and its vast non-profit hydra are trapped between two conflicting forces; they may be swept aside in increasingly desperate fighting between them.

The George Floyd Protests

The Obama era witnessed several large-scale autonomous movements, including Occupy Wall Street, the first wave of Black Lives Matter protests sparked by the revolt in Ferguson, and the struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline.

The election of Donald Trump coincided with a far-right reaction propelled by memes, online misogynist forums, xenophobia, white nationalism, and anti-elitism. This in turn catalyzed a fierce anti-fascist movement. At the high points, it involved millions of ordinary people; but the front-line participants largely emerged from the same social strata as previous grassroots movements, all of which were de-emphasized in favor of building common cause with urban liberals and progressives against the extreme right.

The George Floyd uprising changed all of that. In a matter of weeks, tens of millions of people confronted the police, directly challenging the right of the state to determine what constitutes safety or to defend disparities in access to resources.

Atlanta, Summer 2020: days we will never forget.

In the final days of May 2020, protests and riots spread from Minneapolis to the rest of the country, including Atlanta. For several weeks, thousands of people clashed with police and National Guardsmen near Centennial Olympic Park, constructing barricades, throwing back tear gas canisters, and breaking up the sidewalks into projectiles. On some occasions, large crowds smashed storefront windows, shined lasers at police helicopters, and threw fireworks at police. Every day, dozens of protests rocked the metropolitan area, with revolts also taking place in some suburbs.

On June 12, 2020, two Atlanta police officers killed Rayshard Brooks, who had been sleeping in his car at a Wendy’s. In the following days, determined crowds torched the restaurant. Clashes continued on and off for weeks at the nearby Zone 3 Precinct, then located at Cherokee and Atlanta Avenue in Grant Park, bringing tear gas and explosions to the residential streets almost nightly. Protesters also established a small occupation at the burned-out remains of the Wendy’s.

Amid this unrest, the Attorney General brought murder charges against officer Garrett Rolfe for the killing. In response, hundreds of police officers initiated a citywide sickout, calling out of work and refusing to perform their normal duties. Many officers quit their jobs due to the stress of facing popular opposition and fear of legal consequences for their systematic use of force.

From the beginning of June to the end of 2020, more than 200 Atlanta police officers left their jobs, including the Chief of Police. Some state patrolmen resigned after protesters wrecked their headquarters on July 4, 2020. Some sheriff’s deputies, public transit cops, and affiliated staff also sought new employment. The Georgia Bureau of Investigations has sent out mass recruitment emails to sociology students, suggesting that they too are desperate for more agents. The system faces a crisis of legitimacy and an impossible institutional dilemma as white business owners, landlords, business associations, and international real estate companies demand a crackdown.

This was the context in which the City of Atlanta, the Atlanta Police Foundation, and the office of former Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms developed the plan to build the Cop City. Bundling together cultural nationalism with calls for peace, Mayor Bottoms appealed for calm as her officers dragged students out of cars, beat protesters with batons, and shot tear gas into crowded streets.

The consequences of these events are still underestimated by commentators and activists alike. Some suffer induced amnesia about the revolt; others have moved on to simple commemoration; still others continue isolated but no doubt justified forms of subversive action. Meanwhile, forces in local and federal government, business associations, police departments, and armed militias have continuously worked to make sure a popular uprising does not reoccur.

In addition to passing laws and killing dissidents, this institutional reaction has focused on managing public perception. Industrial interests and private investment companies have conducted influence campaigns using local news outlets—40% of which are owned by Sinclair Broadcast Group, a right-wing organization with ties to former US President Donald Trump. Between Sinclair, Nexstar, Gray, Tegna, and Tribune, this coordinated reframing of events has damaged the way that many sectors of the television-viewing public perceive the revolt and its consequences.

In the wake of the uprising, a false narrative circulated to the effect that the police, demoralized and underfunded, could not control the “crime wave” sweeping the country. This narrative, orchestrated in response to the popular demand to “defund the police” advanced by some sections of the 2020 revolt, has shaped the imaginations of suburban whites, small business owners, and many urban progressives. The “crime wave” framework implied that police departments around the country had in fact been defunded or had their powers curtailed and were consequently unable to assure social peace or free enterprise. In reality, the vast majority of police departments received an annual increase in their budgets, as they normally do. If anything, they accrued more power following the events of 2020, from the political center as well as the right—witness the accession of Eric Adams to mayor of New York City.

The Police Foundation enables corporations to funnel money to law enforcement. Behind every ribbon-cutting ceremony, a line of riot police.

“Institute for Social Justice”

The government of Atlanta has developed a few tentative solutions to the dilemmas they face. To follow through on their commitments to their backers, city politicians need to continue sacrificing public assets on the altar of the economy in order to attract more major investors to the region, especially the film industry and technology companies. To maintain control in a period of rapid displacement and rising cost of living, with chronic tension between the conservative state government and the liberal city administration, they need to funnel more resources towards law enforcement throughout the region. Finally, to appease the increasingly rebellious lower classes, they need to frame this process of restructuring and repression in the language of Black empowerment, social justice, and progressivism.

The bureaucrats are not in a good position to handle this. Decades of tax cuts and deregulation have created infrastructural failures and breakdowns of all kinds. Among other concerns, Atlanta lost the bid for a second Amazon headquarters because the public transit, one of the least-funded in the US, was not even operable when the corporate scouts came to visit. At the same time, it is precisely the low taxes and absence of regulation that attract capital to the state of Georgia, so cultivating a social-democratic governing strategy now may be impossible without creating a flight of wealth to other parts of the country. It seems that the current plan is to give over as many public contracts and resources to private developers as possible, to allow them to incur the costs of social disintegration and anger, to use the police to control the blowback, and to use images of Martin Luther King, Jr. to pre-empt meaningful resistance.

Thus, the plan to transform a wild space into a police training compound is dubbed the “Institute for Social Justice.” The plundering of public assets for the benefit of a movie company and real estate mogul is described as an opportunity to create “good jobs” for local Atlantans, not as a criminal expropriation of infrastructure. The clear-cut that Blackhall Studios plans to trade the city government in exchange for a section of the forest is to be renamed “Michelle Obama Park.”

The government plans to begin clearing the forest for construction in May or June of 2022. What follows is the story of the movement determined to stop this.

Intrenchment Creek Park—future soundstage complex?

Timeline of Events

For the sake of brevity, this timeline does not include lawsuits, injunctions, petitions to stop work, and the like.

Spring-Summer 2021: The City of Atlanta, in partnership with Blackhall Studios, approves the swap of Dekalb County public lands at Intrenchment Creek Park for a parcel of land currently owned by the movie studio. The land deal is conducted in a semi-secretive series of board meetings and hearings.

April-May 2021: Activists and local ecologists uncover a plan by the Atlanta Police Foundation to transform the land known as the Old Atlanta Prison Farm at Key Road and Fayetteville Road into a massive police training compound.

May 15, 2021: Over 200 people gather at Intrenchment Creek Park for an informational session about the development proposals.

May 17, 2021: According to an anonymous statement on Abolition Media Worldwide, seven machines left unguarded on the land parcel owned by Blackhall—chiefly tractors and excavators—are vandalized. Their windows are broken, their tires cut, and they are set on fire. The statement connects the sabotage to the destruction of the forest:

We don’t need a soundstage for entertainment. Everything we need is already there. We don’t need police training facilities. We demand an end to policing… Any further attempts at destroying the Atlanta Forest will be met with similar response. This forest was here long before us, and it will be here long after.

June 2021: Notices appear affixed in the forest notifying passersby that trees in the area have been “spiked,” with the consequence that cutting them could damage saws and possibly injure those utilizing them.

June 10, 2021: Three more excavators are burned on the parcel of land owned by Blackhall Studios. Neither action appears in local news media, although photographic evidence of the damage circulates on social media.

June 16, 2021: On the night that the Atlanta City Council is to vote on the construction ordinance for the “Cop City,” a handful of activists protest outside of the private residence of City Councilperson Joyce Shepherd, the sponsor of the ordinance.

June 23-26, 2021: The first week of action brings hundreds of people into the movement.

August 23, 2021: In Roseville, Minnesota, the windows of Corporation Service Company office are smashed. An anonymous online statement reads,

After smashing the office door and throwing cans of paint inside, a message was left sprayed across the front: HANDS OFF THE ATLANTA FOREST. Demands are being made for CSC to drop their client, Blackhall Studios. Blackhall Studios would like to level the South Atlanta Forest to build the country’s largest soundstage and an airport, creating unprecedented levels of gentrification in the city.

Summer 2021: The Stop Cop City coalition and other left-wing groups join the movement. Grassroots activist organizations and networks create their own demonstrations, social media pages, and meetings. Local independent media outlet Mainline Zine steps up coverage of the movement more or less from the perspective of these organizations.

September 2021: City Council meetings, held on Zoom because of coronavirus-related restrictions, are repeatedly flooded with hours of objections to the project. Votes on the ground-lease ordinance are repeatedly delayed because of these objections and demonstrations at the homes of Atlanta Chief Operations Officer Jon Keen and City Councilperson Natalyn Archibong.

Outside of the home of Natalyn Archibong. Police arresting protesters so that City Council could approve the land lease.

October 7: Color of Change announces that Coca-Cola is stepping down from the Atlanta Police Foundation board.

October 18: A small group of rapid-responders disrupt the surveying and clearing of grounds at Old Atlanta Prison Farm. A surveillance tower is destroyed.

November 10-14: A wide range of cultural events, info-nights, bonfires, and meetings occur during a second week of action. This coincides with the establishment of an encampment in the forest; it lasts for six weeks.

November 12: A demonstration takes place at Reeves Young Headquarters. Intelligence gathering by activists indicates that Reeves Young Construction has been contracted to destroy the forest and build the Cop City development. About 30 people converge at the company headquarters in Sugar Hill, Georgia, holding banners and demanding that the company sever their contract with the Atlanta Police Foundation.

https://twitter.com/defendATLforest/status/1461175735540924416

November 20: Two more bulldozers burn in the forest. According to an anonymous statement republished on the Unoffensive Animal website, anonymous forest defenders

…burnt two bulldozers in the south Atlanta forest. No Copy City, No Hollywood dystopia. Defend the Atlanta Forest.

This equipment was located on the land-swap parcel currently owned by Blackhall Studios, the planned future location of “Michelle Obama Park.”

November 27: A group of Muscogee (Creek) people return to their ancestral lands at the current site of Intrenchment Creek Park in the South River Forest, which, in Creek, is called Weelaunee. The Muscogee delegation calls on everyone to defend the land from the Cop City and Blackhall developments.

December 17: A dozen protesters march to the entrance gate of Blackhall Studios on Constitution Road and block the main entrance, chanting slogans. Shortly after, a large contingent of police raids the forest, evicting the protest camp established there.

December 20: According to an anonymously-written statement republished on the website Scenes from the Atlanta Forest, banners are hung in the backyard of the private residence of Dean Reeves, chairman of Reeves Young. Reportedly, Dean Reeves was among the board members present at the November 17 action and personally shoved and assaulted protesters.

January 9: Survival Resistance, a local environmentalist organization, begins a campaign against AT&T, which is funding the Cop City development, holding protests outside their offices.

January 18: In order to begin “boring” the land, a process necessary for determining the construction supplies needed for laying foundation, Reeves Young and a representative of the Atlanta Police Foundation enter the woods near Key Road and use a bulldozer to knock down many trees. Construction is stopped when protesters demand that they leave. The bulldozer remains at the scene; it is subsequently vandalized, losing its windows.

January 19: Several people climb into tree houses in the forest near the previous day’s confrontation, announcing their intention to remain there in order to delay further destruction.

January 25-27: Long Engineering resumes surveying Old Atlanta Prison Farm, accompanied by the Atlanta Police Foundation, Atlanta police officers, and Dekalb County sheriffs.

January 28: 60 forest defenders march into South River Forest near the Old Atlanta Prison Farm to stop the boring and soil sample collection. Dekalb County Police attack the protesters, arresting four—the first arrests inside the forest in the context of the movement.

Forest defenders light smoke bombs and flares on their way to meet the tractors on January 28, 2022.

January 31: “Autonomous vandals” break windows and spray paint “stop cop city” on a Bank of America in the Twin Cities, Minnesota. According to an online statement, this occurs in solidarity with the protesters arrested on January 28.

March 1: According to another communiqué,

Five large Long Engineering trucks used to do survey work to help delineate destruction in the South Atlanta Forest were destroyed in solidarity with eco-defenders currently protecting the forest from being clear-cut to build cop city and more Hollywood infrastructure for Black Hall Studios.

March 19: Six machines owned by Reeves Young, including two large excavators and a bulldozer, are destroyed in Flowery Branch, Georgia. The online communiqué reads:

Unless your company chooses to pull out of the APF’s Cop City project of its own volition, we will undermine your profits so severely that you’ll have no choice but to drop the contract.

March 26: Wells Fargo and Bank of America ATMs are vandalized in City Center, Philadelphia. According to an online statement, both institutions were targeted because they fund the Atlanta Police Foundation.

https://twitter.com/unoffensive112/status/1509418720493453318

Coming Out with a Bang

Movements usually take one of two common paths from inception to peak to decline.

The first possibility is gradual escalation. This is the model commonly embraced by activist organizations, labor unions, student groups, and the like. In this approach, movement organizers or cadres initiate meetings and protest actions designed to walk as many people as possible through the contradictions inherent in the reformist process, slowly introducing the participants to the need for additional methods.

When this strategy goes well, an experienced movement then initiates a sequence of broader and more militant efforts focused around particular demands or aims. In the austerity era, however, it is very difficult to compel the authorities to grant demands; more frequently, police repression, charismatic careerists, and attrition all contribute to the slow deceleration of the struggle. In regions or companies that are experiencing substantial economic growth, movements are sometimes able to win their demands, but this generally comes at the expense of the mobilization itself, involving the co-optation of movement leaders, the criminalization of effective tactics, and the subsequent restructuring of resources and institutions—for example, in the form of automation or outsourcing.

Alternatively, it sometimes occurs that a movement erupts into the spotlight with a sudden concussive gesture that draws attention and power into a kind of vortex of refusals. Such struggles are often catalyzed by single issues or grievances that rapidly become paradigmatic of all social ills. Most of the mass revolts that have broken out since 2019 have followed this path, including the so-called October Revolution in Chile, the George Floyd uprising in the US, the revolt against Omar Bashir in Sudan, and the 2022 uprising in Kazahkstan. By escalating into a general clash with all forms of power, the protagonists of these struggles indict the entire social order, posing the question of revolution in practical terms. To date, however, most such uprisings have been crushed by police, swallowed by civil wars, or annihilated by geopolitical superpowers.

Thus far, the fight to defend the Atlanta forest does not fit either of these patterns. It may represent a different trajectory, suggesting a way forward for struggles after the tumultuous events of 2020.

“Barricades close the path but open the way.” A blockade defending the forest.

First, Attack Their Strategy

In April 2021, when activists discovered these two proposals to destroy the South River Forest, they spread the news via word of mouth for several weeks about a large information sharing session at Intrenchment Creek Park. Around 200 people attended this initial event. The city government had yet to announce its plans publicly, so the opponents were able to craft the public narrative themselves, ensuring that the facts didn’t get lost in the shuffle. At the information session, multiple masked presenters contextualized the development within an overall schema of 1) racist and authoritarian backlash against the George Floyd protests, 2) pan-urban gentrification and displacement processes, and 3) climate collapse and the long-term future of the region.

With this event, event organizers denied the city government the opportunity to introduce the developments to the public with a distorted narrative—assuming they intended to publicize them at all. Attendees asked questions, shared perspectives, and committed themselves to sharing what they had learned with their communities while organizing grassroots, bureaucratic, and direct resistance. This established basis for a collective struggle that could utilize multiple strategies and tactics.

Within 48 hours, saboteurs destroyed seven unguarded excavators, tractors, and other pieces of heavy machinery. An anonymous statement appeared online detailing their motivations and methods and connecting the attacks to the struggle against colonialism, authoritarianism, and gender normativity. This catapulted the movement into its first phase of development. To date, no one has been arrested for these actions.

Over the following weeks, meetings, posters, and fliers spread throughout left-wing networks, farmers’ markets, and do-it-yourself subcultural spaces. Local ecologists and folk historians with long-term investment in the land organized tours and plant identification walks. A few candidates for City Council adopted the struggle as a component of their electoral campaigns.

In mid-June, saboteurs published another statement announcing that a number of trees had been “spiked” and three more excavators had been damaged. The sabotage occasioned no dismay among the opponents of the development. Rather, because it occurred so early in the movement, this kind of bold action became a part of its genetic material. While many people celebrated these actions, it remained to be seen whether the movement would develop a participatory strategy enabling more people to take action beyond sharing information or cheerleading the courageous deeds of anonymous activists.

If the participants in the first phase of the movement had aimed to create a political scandal, they had not succeeded yet. However, they had drawn the attention of a few hundred people who were willing to support a movement that included vandalism and other forms of sabotage. They had also established a discourse about the forest on the terms set by autonomous activists, not politicians or police.

What was missing in the first phase inversely structured the phase that followed.

Intrenchment Creek Park.

Names and Addresses

By mid-June 2021, most of the grassroots left as well as autonomous, anarchist, and radical groups in Atlanta were aware of the proposed developments in the forest, but they were still searching for strategies that would enable them to build enough power and leverage to halt the projects. Some people—including activists connected to nationwide socialist organizations, abolitionist networks, and ecological advocacy groups—began knocking on doors in the vicinity of the South River Forest, reasoning that neighborhood organizations and households around the forest would be necessary allies, as they would be among those most impacted by deforestation and sound pollution. The canvassers hoped to familiarize themselves with the discourse of the neighbors and learn what might help to mobilize them.

Other strategies emerged around the same time. One group focused on the City Council meeting of June 16, which was supposed to vote on the land-lease ordinance sponsored by then-Councilperson Joyce Shepherd. Because the meeting occurred online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the City Council members hosted their conversation from their respective residences. With a bit of research, a handful of protesters located the home address of Councilperson Shepherd. This group went to her home and displayed a banner during the meeting. While the majority of the protesters chanted from the sidewalk, one individual approached her house, knocked on the door, and rang the doorbell before returning to the street. Inside, unbeknownst to the protesters, Shepherd was panicking. Those in power typically assume that their actions occur in an abstract political “space,” and that the consequences of their decisions will not directly impact them. Shepherd called off the vote and left the meeting early to call the police, who arrived after the protesters had dispersed.

In the hour that followed, Joyce Shepherd held a press conference from the newly constructed Zone 3 Police Precinct on Metropolitan Parkway. At the precinct, Shepherd was surrounded by police officers and news media. She described in detail the aims of her land lease ordinance, the nature of the project, and the efforts of protesters to stop her. With this short statement, she catapulted the movement and its story into the mainstream. The following day, she made another statement in which she claimed that she would push through the ordinance “no matter what” the city residents that she ostensibly represented had to say. Her fellow representatives rejected the tactics of the protesters, falsely implying that their methods were illegal.

With this action, a few people were able to accomplish an early goal of the movement—to transform the Cop City/Blackhall developments from back-door agreements into public scandals. They also delayed the vote, concretely displaying the potential of direct confrontation. A new strategy was emerging: to pressure decision-makers directly.

Intrenchment Creek Park walking path. Resistance in every inch of the forest.

First Week of Action

The first planned Week of Action began a few days later, on June 23. The organizers hoped to catalyze a wide array of interventions. They held meetings to explain their ideas, aiming to interconnect resistance against the Cop City development, the Blackhall development, and the accompanying gentrification and deforestation. Some set up a shared calendar and online promotion plan so that more people could step forward to express themselves in the context of the movement.

In this regard, the first week of action was a resounding success. In the course of the week, there were conversations about ecology, colonialism, and sexuality; there were guided tours by day and by moonlight; there were nightly bonfires in a forest clearing; there was a hardcore punk show at a nearby venue, during which hundreds of participants repelled police; and there was a rave party deep in the center of the forest, gathering some 500 attendees in a utopian ambience illuminated by glow sticks and lasting into the early morning hours. If the organizers had set out to generate a cultural consensus among the thousands of people in the city’s DIY art, poetry, queer, punk, and underground dance subcultures, they succeeded.

On the night of June 24, people visited the home of Blackhall Studios CEO Ryan Millsap in the outer Atlanta suburb of Social Circle. Activists hoped that placing fliers at the home, street, investment properties, and post office box of Millsap would, in their words, “inspire others to research and take the fight to those directly responsible for the destruction of the forest.”

Two days later, on June 26, the final day of the first week of action, fifty or more protesters marched to the headquarters of the Atlanta Police Foundation (APF). As the crowd emerged from Five Points metro station, a small contingent of officers attempted to arrest someone. The crowd engaged in hand-to-hand fighting with the police and successfully repelled them. Continuing behind a banner reading “Another Word for World is Forest,” a reference to the Ursula K. Le Guin book The Word for World is Forest, the group descended on Deloitte Tower on Peachtree Street. Advancing past security, they marched straight to the APF office and smashed the glass doors and windows before overturning tables in the tower lobby. The participants successfully dispersed into the city center without arrests, while dozens of police vehicles frantically established a perimeter—effectively shutting down the central downtown corridor.

Corporate media coverage of the action at the headquarters of the Atlanta Police Foundation on June 26, 2021.

When Dissent is Not Enough

The movement expanded over the following months. New organizing groups were announced as activist organizations and independent media outlets developed a framework enabling them to orient themselves to the struggle. While corporate news and the Police Foundation failed to present a coherent media narrative following the vandalism of the APF offices, organizers got to work circulating informational fliers and online graphics, conducting interviews, knocking on doors, and organizing phone-in campaigns during subsequent City Council meetings. For nearly all of August and September, the “Stop Cop City Coalition” and others worked to introduce tension and contest the City Council process. Following the intervention at the home of Joyce Shepherd, protesters gathered outside the homes of possible “yes” voters on the nights that the vote was slated to take place, causing further delays in the process. For a moment, it seemed possible that the campaign could achieve an easy victory.

Unfortunately, it was not to be. As those who study revolutionary movements know, the police perform an essential function in class society, without which many other hierarchies and exploitative relations could not exist for long. This is not simply an economic or civic issue that can be worked around with some clever ideas and a bit of pressure. Despite the efforts of organizers, which culminated in 17 hours of oppositional public comment, the ordinance was passed on September 8 while police arrested protesters outside the home of councilperson Natalyn Archibong. The land hosting the Old Atlanta Prison Farm was turned over to the Atlanta Police Foundation.

Many sincere people were demoralized by this turn of events. Some turned their attention to the upcoming local elections, hoping that the city government could be stacked with abolitionist or progressive candidates who might strike down the project. As it turned out, Mayor Bottoms did not run for re-election, and the former mayor, Kasim Reed, lost to current mayor Andre Dickens. Joyce Shepherd also lost her campaign for re-election. Yet since the elections, nothing has changed regarding the Blackhall and APF developments.

Outside of the home of Jon Keen, Chief Operations Officer of Atlanta Government.

The Fight Is On

The Atlanta Police Foundation has contracted at least three companies to build their compound. The surveying appears to be the work of Long Engineering, while the construction itself is to be done by Reeves Young Construction and Brasfield & Gorrie. It is not clear yet who will clear the land in Intrenchment Creek Park, where Blackhall Studios hopes to expand.

The information that is known to date was hard won by diligent activists on the ground. Shortly after the City Council vote in September, surveyors and small work crews began entering the site near Key and Fayetteville Roads. The trucks and uniforms revealed the names of the contractors, which once again gave opponents of the Cop City the chance to initiate a struggle on their own terms.

On October 8, about two dozen people entered the work site from the forest and confronted contractors who appeared to be clearing land for the purposes of taking photographs and samples. When the workers left, a surveillance tower erected by the police was toppled. Forest defenders dispersed with no detentions.

Had forest defenders utilized only virtual or bureaucratic channels to collect information, they might not have learned that Reeves Young were being called in to do the actual destruction until it was publicly announced much later. The ability to break news to the public before the city government has been a consistent advantage.

Second Week of Action

It’s a widely observable point of failure in movements when the protagonists lose the initiative and resort to attempting to recreate an earlier phase of events. Nostalgic for the heady days of open revolt, the chaos of fiery nights and smoke-filled shopping districts, people resolve to call together a coalition of the willing to kick things off again. Hoping it is enough to set a clear time and place, preparations are made, and a crowd assembles—but falls short of expectations, consisting chiefly of dedicated militants or friends.

As the weeks pass, this becomes the new high-water mark. With a more serious attitude, a group of friends or a network of crews calls together another demonstration “like the last one,” but perhaps in a different location or with a more ambitious intention. This may work a few times—but new roles and rules of engagement are being established, the euphoric sense of power that animated the early days is gone, and nothing can bring it back. The large crowds have dissipated and the police are learning every step of the way. Eventually, even this comes to an end, and the participants devise all kinds of theories to explain why. The conclusion typically involves finger-pointing, resentment, denunciations, and splits as the rebels blame each other for their shared failures and limitations. An entire book could be written about this phenomenon. But if participants in struggles can become aware of this general tendency, that awareness might open up space for more creative efforts.

Following the City Council defeat in September, it wasn’t clear how many people would continue to oppose the developments, though the small confrontation on October 8 suggested that some wished to. Sensing the difficulty of this moment, organizers announced a second Week of Action for mid-November.

The second Week of Action was similar to the first, but there were innovations. Once again, various groups organized cultural events, information nights, bonfires, and meetings—but this time, many of these occurred in or near a more publicly advertised encampment at Intrenchment Creek Park.

https://twitter.com/defendATLforest/status/1458631384931700739

The organizers of the first Week of Action had welcomed a small cluster of participants to camp, essentially in secret, on a stretch of the Old Atlanta Prison Farm. This time, a few dozen people pitched tents, erected tarps and make-shift kitchens, hung banners, and constructed a bona fide protest camp in the woods. This camp persisted in some form for six weeks. Unsurprisingly, the overall diversity of those who gathered had decreased compared to the first week of action, a general tendency of movements and mobilizations. When a struggle contracts as a consequence of disorientation, repression, or other setbacks, the movement oriented towards it often divides back into its constitutive elements, usually along ethnic, generational, gender, and class stratifications, despite the efforts and good will of the participants.

Taking the Fight to Them

Now that Reeves Young had been identified as the contractor hired to destroy the forest and build the police training compound, many participants in the movement shifted to focusing on them. On November 12, 2021, immediately after the second Week of Action, thirty people descended on their offices in Sugar Hill, Georgia, forty miles outside of Atlanta. Holding banners and chanting slogans, this group walked right into the offices, disrupting a board meeting involving company president Dean Reeves and CEO Eric Young. The executives did their best to appear unfazed, commenting on the millions they would line their pockets with. Slowly, the atrium filled with workers concerned about the protests and the aggression and violence of their bosses, who had begun shoving and even punching protesters, going out of their way to target the smallest people present. The protesters had already accomplished their goal of applying direct confrontational pressure to the Atlanta Police Foundations service provider.

Three days later, two more excavators were burned on the parcel of land currently owned by Blackhall studios. These were the eleventh and twelfth pieces of heavy machinery to be sabotaged, reckoning by the claims of responsibility that appeared online. Unlike the previous anonymous statements, the statement accompanying this action was succinct, stating only what had occurred and why.

The movement had faced setbacks, but it had not collapsed into a private grudge match between hardened militants and the Police Foundation.

Stomp Dance

On November 27, 2021, 250-300 people gathered in Intrenchment Creek Park to observe and participate in a ceremonial stomp dance and service of the Muscogee (Creek) people. This particular delegation came from the Helvpe Ceremonial Grounds in eastern Oklahoma, invited to their ancestral homelands by a local indigenous organizer.

The Muscogee people were once organized into a confederation of tribes spanning much of what is now Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina. The Muscogee peoples and their Mississippian ancestors in this region, known as “mound builders,” maintained a network of towns, each preserving political autonomy and territorial independence, allocating resources and making decisions in a consensus process unknown to their later European antagonists. The concept of private property that reigns supreme in our society was anathema to the Muscogee peoples, who held essential goods and lands communally. Nearly all of what is now Alabama was taken from the Muscogee in 1814, following the defeat of the Red Sticks revolt in which many Muscogee people allied with Tecumseh and the insurgent Shawnee peoples against colonial expansion into their communities. Between 1821 and 1836, the Muscogee were forcibly removed from their homes to Oklahoma, where many still live.

When the November 27 delegation came to the South River Forest, or Weelaunee, to perform their dances and speak their language, they shared some of their knowledge and histories with those gathered. But their goal was not simply to share culture in a depoliticized way. They encouraged the current residents of Atlanta to stop the destruction of the forest and halt the Cop City and Blackhall developments, understanding these as the latest chapters in a long story of destruction beginning with the European colonization.

The Muscogee (Creek) delegation performs a stomp dance in the Weelaunee Forest on November 27, 2021.

Moves and Counter-Moves

In the weeks following the ceremony at Intrenchment Creek Park, participants in the encampment in the forest outfitted it with a field kitchen and sitting area and erected banners and signs in the forest visible to mountain bikers, hikers, and others who passed through the park. Establishing a semi-permanent presence in the forest was a way to gather information on an ongoing basis and to provide an immediate deterrent to developers.

The encampment was evicted on December 17, after six weeks. That morning, about a dozen people blocked the entrance to the existing Blackhall Studios site, located on Constitution Road. This contingent subsequently burned a flag, chanted slogans, and “hexed” the media company before dispersing into the forest. In the following hours, presumably at the urging of Blackhall, Dekalb County Police entered the forest en masse, mobilizing police cruisers in the parking lot, officers on foot, helicopters and drones overhead, and unmarked vehicles on the streets. The officers were likely intimidated by the low-visibility terrain; in any event, all of the forest defenders based in the encampment escaped without being detained. This was the first time a concerted effort was made by law enforcement to engage protesters in the South River Forest.

A month later, on January 18, 2022, Reeves Young and the Atlanta Police Foundation entered the forest near Key Road with a bulldozer. They began knocking down trees so that their associates in Long Engineering could survey the land, placing stakes and marking trees for removal. Approximately a dozen people in dark clothing approached the workers and APF representative Alan Williams, ordering them to leave. The bulldozer was subsequently vandalized.

Several people quickly built multiple impressive tree houses near the surveying site and climbed into them. News of this new tactic spread rapidly. It couldn’t have come at a better time.

https://twitter.com/atlanta_press/status/1510278635705487363

The Stakes Go Up

In the confrontations with contractors on October 8 and January 18, small, dedicated groups were able to halt work without resorting to force. It is possible that this period has ended, or else that the timeline for surveying and sample boring now requires business executives and police chiefs to expose their employees to greater risks in pursuit of their respective bottom lines.

From January 25-28, repeated efforts were made to stop tree felling and soil boring, all to no avail. In some instances, only a handful of activists were on the scene behind makeshift barricades. Reinforcements could not arrive rapidly enough to assist those on the ground. Later in the week, on January 28, around 60 people marched to defend the forest at 10 am on a weekday. This crowd, the largest to gather in any one place in many months, marched into the forest, onto the Prison Farm property, around erected barricades and tree houses, and directly confronted construction workers who were boring holes in the ground.

Police attacked the march, tackling several people; the other demonstrators did not mount a proportional response to this aggression, despite outnumbering the police. Perhaps some of the tactics popular during the 2020 rebellion, such as mass use of umbrellas or makeshift shields, could have equipped the participants to feel more capable of decisive action. Alan Williams of the Atlanta Police Foundation was filming protesters, looking a little anxious as he did so.

This was the first time that protesters were arrested in the South River Forest, on either the Prison Farm or Intrenchment Creek sides. Each new phase of the movement has been constructed out of elements missing from the phases that preceded it, developing out of the contradictions and limits of the previous phase. It may be possible to chart a new path forward from this point starting from the most resilient aspects of the previous stages.

They go low, we go high. A treehouse in the forest.

The Best Defense is a Good Offense

Every movement needs both offensive and defensive strategies. In this case, defensive strategies would enable activists to withstand repression and protect the forest. Offensive strategies would enable activists to impose their own timelines, battlegrounds, and confrontations, demoralizing those who seek to destroy the forest and eventually forcing them to abandon the planned developments.

https://twitter.com/defendATLforest/status/1494339171887943690

Defense

As of the beginning of April, it appears that on-the-ground resistance to construction is not currently a viable offensive strategy. The presence of activists and organized groups in the South River Forest should be understood as the most sophisticated defensive strategy available to the movement. The forest will remain a site of contestation as long as the APF and Blackhall Studios seek to destroy it. The more activists understand the forest and its specific terrain, the more prepared groups will be to carry out actions there; the more practices and infrastructures participants establish that newcomers can make use of, the better. By continuously connecting a struggle to the fate of a particular place, participants foster an emotional and sensuous relation to the land that is seldom found in movements around abstract goals.

Some components of a coherent and efficient defense:

- Hold decisive terrain. Reeves Young and Blackhall hope to destroy a particular area of forest. By preventing them from easily operating in this location, making it difficult to survey it and dangerous to leave equipment there, a defense strategy can severely limit their ability to accomplish this.

- Attrition. Recognizing this terrain as the defensive position, forest defenders could drag Reeves Young, local police, or other adversarial forces into narrowly focused and labor-intensive conflicts, games of “cat and mouse,” and other expensive and unrewarding engagements. For now, the defenders possess an advantage in this regard, because the terrain itself can be prepared to frustrate the efforts, ease of movement, visibility, or general operating capacity of the attacker. The more the adversary has to surveil and plan around the defenders, the less they can focus on destroying the forest.

- Disruption: Forest defenders can limit the ability of the adversary to attack according to coherent or synchronized schedules or timelines. Defenders have the privilege of selective engagement—they can engage when and how they please, according to inclination or opportunity, putting the attackers in a state of uncertainty.

- Preparation. The primary purpose of defense is to open space for offense. Forest defenders can carry out stationary or mobile operations; they can engage or escape; they can disrupt, sabotage, confuse, or misdirect the developers. The chief goal is to force the developers to proceed in a clumsy and confused manner both logistically and politically.

Defense cannot substitute for offense, but it is a necessary aspect of all fights. If on-the-ground defense becomes the sole focus of a movement, that movement will eventually be defeated. In this case, that would mark a step back from the beginning of the movement, in which the participants set the terms of the entire conversation. If large-scale development does not begin for many months, it could be disastrous for embattled activists to spend that period accumulating charges and injuries fighting uphill battles against an increasingly emboldened and militarized opponent.

Therefore, other means are necessary.

https://twitter.com/efjournal/status/1503767540463329281

Offense

Whoever sets the terms of a fight can arrange the dynamics to the disadvantage of their adversary. When police drive hostile crowds into empty corridors, parking garages, or alleys, that is what they are trying to achieve. This is what governments do by continuously framing conflicts as discrete “issues” and “debates,” conferring agency to those best situated for generating public consensus and structuring the consumption of information (i.e., politicians and the electoral machinery that promotes them). For those with less means, the best strategies catch their opponents off guard, compelling the adversary to respond in ineffective or imprecise ways. Ideally, the adversary should not even understand what is happening.

Participants in direct-action-oriented movements generally have an overdeveloped focus on offense. Gathering information, audacious frontal engagements, surprise attacks, swarming tactics, hit-and-run maneuvers, striking unprotected targets or infrastructure, targeted online campaigns, setting the pace with both concentrated groups and decentralized crowds… all of these are more or less familiar to those experienced in riots, rebellions, and direct action campaigns over the last decade.

Yet there is more to say about the principles of offense and how they relate to this movement.

Old Atlanta Prison Farm. The land has been slowly healing from centuries of violence.

Movement Diversity Is an Asset

To date, the movement to defend the Atlanta forest has not coalesced around a single coherent strategy. The participants have employed several parallel strategies in tandem, with the strengths of one approach filling in for the weaknesses of another. This works best when the participants tolerate those with different tactics and priorities. In a movement that accommodates a diverse range of approaches, particular strategies can succumb to “evolutionary pressures” without that jeopardizing the movement as a whole.

As alluded to earlier, there have been tensions in the movement regarding the priorities of different groups, the presumed identities of the participants, and the alleged connections between their respective experiences of oppression and their political ideologies. At times—and this is hardly unique to this movement—single-issue mentalities have undermined some participants’ ability to imagine a struggle cohering around overlapping but distinct aims and motivations; at worst, this has led some to claim that those with different priorities are not worth collaborating with. Many movements have been hamstrung by this kind of mentality over the past half decade—and police departments, city governments, reactionaries, and liberal opportunists have not missed the chance to exploit this. Both experience and common sense suggest that it is not wise to place all of one’s eggs in one basket—and that redundancy is not always a sign of disorganization, as some centralizing tendencies imply, but can be an expression of a more resilient approach to organization, as long as the general goals remain in focus.

Critical, inquisitive attitudes will generally serve us better than any form of dogmatism. If one group or tendency can accomplish their goals alone, then let them do so. Since none has, yet, in this case, it must be necessary to work alongside others, even if one would prefer not to. If one can only work with those one can bully, intimidate, or shame, it should not be surprising if one’s allies lack conviction, courage, and intelligence. The clear articulation of differences, criticisms, and concerns is a strength in movements, but ideally, they should be articulated in a spirit of mutual education and learning, lest they become a part of the repressive landscape itself, serving police and developers as various tendencies and cliques slowly cannibalize each another.

https://twitter.com/defendATLforest/status/1452666819240734728

The SHAC Model

In this general spirit, it is worth spelling out a strategy that has been latent in the movement since last fall—from the demonstrations at the houses of Joyce Shepherd and the other city council representatives to the pressure directly leveraged against Reeves Young and Ryan Millsap of Blackhall Studios. This approach could be summarized thus: hold those responsible for these projects personally liable for their decisions and the decisions of the companies they own. Because the entire system of rules and norms we live under dictates that exploiters, warlords, mass murderers, and those who destroy ecosystems must not face pressure at home as a consequence of the decisions they make at work, this strategy is bound to be controversial. It rejects the entire logic of “limited liability” that forms the basis of corporate rule in our society.

At the beginning of the 21st century, animal rights activists in the United Kingdom and the United States set out to take down the biggest animal testing corporation on the planet, Huntingdon Life Sciences (HLS). The campaign to stop HLS, “Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty” (SHAC), formally disbanded in 2014, is best known for its period of ambitious international participation in the early 2000s. The methodology of this movement, which encompassed direct action, symbolic protests, cultural events, sabotage, pranks, and more, included many features that have since been used in a wide range of campaigns. The overall strategy of SHAC involved mobilizing a few hundred people to maximize their effectiveness against a major enterprise by focusing only on their ability to function economically. The methods and outlook of the “SHAC model” could be instructive to opponents of the Cop City and Blackhall Studios development in the South River Forest today.

The SHAC model is centered around tertiary targeting, i.e., isolating service providers from third-party contracts in order to limit their ability to provide services to the client, which is the actual target.

The SHAC model isolates the service provider (e.g., Reeves Young and whoever is contracted for Blackhall) from all their third-party clients: from the other construction contracts they have, from the companies that manage their landscaping or data, and from any company that provides them labor or supplies.

The service provider depends on many third parties. Those third-party contracts provide the service provider with insurance, materials, equipment, security, catering, cleaning, mail service, data maintenance, and more. All of those third parties can be pressured to drop the service provider. Furthermore, the service provider is likely a company with more than one client, and those other clients can also be pressured to drop the provider. Any company or contractor that is able to move their money away from the service provider because they have other economic opportunities can be pressured to do so.

Essentially, this strategy does not directly challenge the bottom line of any of the third-party companies; it only isolates and demoralizes the service provider and, therefore, the client. To date, it remains uncertain who the service provider is for Blackhall, although that information will come out sooner or later.

https://twitter.com/defendATLforest/status/1483867828935610380

Limits of the SHAC Strategy

In actions outside the forest—at some distance from the object of their efforts—it might be more difficult for activists to maintain a sense of urgency. Targeting individuals at their offices and homes will chiefly bring out those who are excited about such confrontational methods, rather than those who prefer to maintain welcoming spaces of encounter, to build tree houses or clean campsites or cook for others, to cultivate the kind of collective imagining that is needed to transform society.

If they fail to do proper research or mapping, activists could waste time targeting minor institutions and companies that are unwilling or unable to drop their contracts. They could spend months facing down insignificant companies with many possible replacement subcontractors. The forces bent on destroying the forest may be able to ensnare activists in legal battles. Laws are always biased in favor of profiteering.

Participants in this kind of strategy sometimes develop a warped idea about the nature of power. While our society is ruled by corporations and states, and those entities are run by real human individuals, patterns of exploitation, abuse, destruction, and violence are not simply caused by the malevolence of specific people. Holding individuals responsible for their actions can be an effective tactic in protest campaigns, but the ultimate goal is to emancipate all humanity and the earth, including those who profit on the current arrangement, not to pass judgment or punish evildoers.

All real proposals can be put to the test through practice and judged by the outcome. The proposal to employ this strategy to defend the forest is built on a simple hypothesis: if Reeves Young is forced to drop the contract with APF, APF investors will lose the confidence required to find a replacement and the project will fail. The same goes for the Blackhall project. If activists defeat Reeves Young by means of direct action and self-organization, even if the project finds a new contractor, the sophistication and confidence that the movement will have developed in the process will likely help it to evolve once again.

https://twitter.com/defendATLforest/status/1473374883811934211

Learning Lessons: I-69 and NODAPL

Many struggles against infrastructure projects have taken place in the United States over the past two decades. Grassroots movements have halted pipelines, industrial developments, new jails, mountaintop removal projects, and deforestation efforts. We can also learn a lot from movements that failed, such as the fight to stop the construction of Interstate 69 and the struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline in Standing Rock.

In the movement against I-69, the so-called “NAFTA superhighway,” a small group of anarchists and environmentalists developed a strategy focused on material disruption. Utilizing direct action and outreach efforts in the part of southern Indiana where the construction was slated to begin, activists hoped to nip the project in the bud. In the end, the industrial interests behind the highway project out-maneuvered the autonomous groups and their allies. The strategy of nipping the project in the bud committed organizers to extending themselves hours away from their homes, in an often hostile region. They were able to build strong relationships with the farmers directly facing land seizures by the highway, but the FBI worked to isolate those farmers by visiting their churches and speaking with pastors who did not feel threatened by the highway but were primed for anti-anarchist panic. Had those organizing against the highway done more to build momentum and participation further along its projected route, in friendlier farming regions, college towns, and larger cities further north, it is possible that a broader and more robust struggle could have emerged. This strategy would have relied on digging in and inhabiting camps over the years that it took for the state to reach them, rather than attempting frontal confrontation at the beginning of construction.

In the movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline, a powerful network of Indigenous groups, environmentalists, anarchists, and protesters coalesced alongside spiritualists, lawyers, and local politicians seeking to stop the construction of an oil pipeline across Lakota lands. Despite the efforts of early organizers and activists, the movement generally centered the voices of trained activists and politicians operating within the colonial structures over the voices of young people and working-class Lakota people in general. This contributed to a tendency to condemn effective tactics—“nonviolent” or otherwise—in favor of symbolic actions and legalistic strategies.

In the end, a confusing series of announcements by then-President Barack Obama implied that the movement had succeeded, when in fact the construction was only delayed. After this, David Archambault and others within the movement utilized identity-based arguments to demobilize the encampments and disaggregate the movement as a whole. Archambault was rewarded generously for playing this role, while other participants in the movement were imprisoned. This coincided neatly with the strategy of Tiger Swan, the private security contractor hired by the pipeline company, which aimed to divide the camp along lines of identity in order to polarize it and isolate radicals.

The defenders of the Atlanta forest should continue to invest in mass-oriented strategies, not specialized campaigns, using cultural means to cultivate the kind of widespread support that will enable them to replenish numbers and withstand repression. At the same time, they should popularize decentralized tactics that directly empower individuals in order to limit the damage that authoritarians and opportunists can inflict on the movement.

Forest Defenders confront Long Engineering and Dekalb County Police.

The Shock of Victory

We win more than we realize. Across twenty years of resistance, expressed in direct action movements on both “local” and “global” scales, attitudes have shifted throughout our society. The efforts and ideas of social movements have been instrumental in this transformation. We have seen the results in widespread approval of Indigenous and environmentalist resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016, in the unprecedented participation of white and non-Black youth alongside Black rebels in the George Floyd Uprising of 2020, and in the general consensus, across an entire cross section of political tendencies, that the neoliberal order that existed from 1980 on is in crisis and that a new chapter in world politics is desirable as well as inevitable.

In many environmental defense movements, it is very difficult to accomplish the short-term goals; the protagonists often proceed as if they do not expect to win. The mid-range goals, though rarely articulated aloud, typically include more general aims such as:

- discourage future ecologically destructive ventures

- de-legitimize authoritarian organizing strategies

- demoralize or challenge the legitimacy of police forces and institutional channels

- innovate or spread direct-action-oriented frameworks or tactics

- spread radical ideas and extend the networks of those who espouse them.

When we consider the past decade through this lens, it is hard to argue that anarchists, abolitionists, anti-fascists, environmentalists, feminists, prison organizers, and Indigenous and Black radicals have failed. Some of these goals have been achieved to such an extent that tactics and proposals that were confined to the radical fringe 20 years ago have been adopted by millions.

Long-term goals—world revolution, decolonization, the abolition of capitalism, the destruction of borders and racial hierarchies, the abolition of police and standing armies, the advent of real community—do not seem immediately attainable, but they too may be closer. Since 2018, according to the International Monetary Fund, the tides of revolution, insurrection, upheaval, and mass disobedience have reached historic proportions. Thus far, most of these rebellions have been suppressed or appeased, confirming the classical revolutionary doctrine that only a worldwide revolution can truly emancipate us, as the ruling order now commands forces of repression with global reach. Nonetheless, as we are seeing in Ukraine right now, there are limits to what even the most powerful of those armies can do.

But what about those of us engaged in concrete struggles today, struggles we are determined to win? Paradoxically, it appears that nowadays, it is easier to achieve mid-range goals than short-term goals, and people focus on long-term goals more often than short-term ones. Somehow, thousands have participated in destroying shopping districts, establishing temporary cop-free zones, and blockading airports, but it is still very difficult to imagine protecting a single wildlife corridor at the outer limits of one city. This is unnerving, but it should not be demoralizing. As we have already seen, it is more likely that thousands of people will rip up paving stones and use them to fight the police than it is that the Atlanta City Council will heed the demands of its own constituents. It was precisely this dramatic sequence of events, spiraling outward from the ruins of the Third Precinct in a storm of riots, that made it possible to talk about restructuring law enforcement across the country—not the reformist organizing campaigns of the preceding decades.

In light of this, those dedicated to defending the Atlanta forest find themselves in a difficult predicament, though not an impossible one. On the one hand, they must develop a framework that distributes agency broadly—something that many groups can participate in and influence. The aims of these groups must be immediate enough that small victories can enable people to build confidence and momentum. And they must proceed as if victory is possible—for surely, it is—while bearing in mind that another revolt against the police, gentrification, climate collapse, or racism could erupt everywhere, informed by experience emerging from a struggle that is, for the time being, a local affair.

This is an immense responsibility—and a gift. The influence of intentional groups and organizations can get lost in the chaos of massive uprisings, as millions take hold of their own lives. Yet in the past decade, we can see how the innovations of radicals and small groups in local movements can shape the imaginations of the mass movements that follow. The defense of the Atlanta forest will influence struggles to come. What we do now will set a precedent for what happens later. Let’s not back down.

No Cop City, No Hollywood Dystopia!

https://twitter.com/defendATLforest/status/1513380231460974597

Appendix: The Atlanta City Prison Farm and the Legacy of Carceral Reformism

In 1821, after coercing the Muscogee to leave Georgia in a forced march, the government of Georgia extended a rail line west to the area near the border of Muscogee and Cherokee lands, where the city of Atlanta now sits. Industrial development was a major contributing factor, including the desire to establish trade outposts and a national rail system connecting the agricultural zones of the South with the industrial zones of the Northeast.

Using labor and infrastructure from neighboring Decatur, which had been established in 1822 following the seizure of Muscogee territory, residents and businesses rapidly expanded around the terminus of the rail line. It became a major logistical hub, arguably the biggest in the southeastern United States.

In 1864, during the US Civil War, Union General Sherman attacked Atlanta, torching nearly all of the railway and surrounding buildings, effectively destroying the capacity of the Confederate Army to move troops and resources through its territory. In the years following, the population of Atlanta exploded. It became one of the largest cities in the Southeast, with a large Black and working-class population.

During Reconstruction, the borders of the city expanded to accommodate the waves of new residents, including emancipated Black people arriving from plantations. With this growth, the power of the municipal government expanded in conjunction with local capitalists’ efforts to attract investments to the new state capital. The government was given the right to open public workshops, mills, factories, and parks.

In 1920, the government of Georgia turned a municipal dairy farm located on Key Road into a jail. The transformation of the dairy works from city-owned factory into forced labor camp illustrates the relationship between production and statecraft in the US. Despite the hopes of early reformers and ideologues, the state is not a vehicle for conflict resolution, nor an instrument for class reconciliation, nor a means of establishing social peace. The chief function of the state is to enforce hierarchies in knowledge (sacred, legal, or otherwise), control of resources (including land, raw materials, capital, means of production, labor, armies, and the like) and decision-making (bureaucracies, courts, congresses, and so on). As long as a state controls a territory, it will reserve the right to transform any element of that territory into a police operation or facility.

We can see this in the history of the former dairy works on Key Road. As the Atlanta Community Press Collective documented in their 2021 article, “Slave Labor, Overcrowding, and Unmarked Graves”, the Atlanta City Prison Farm rebranded itself again and again over the following years, while extending its authority and resources under successive phases of “humanitarian” reforms and restructuring.

In the beginning, the opening of the Prison Farm was justified by a false narrative about economic stagnation at the dairy works, as well as moral outrage surrounding the egregious conditions at a nearby stockade on Glenwood Avenue. Subsequently, in 1944, the prisoners were forced to erect a new building, a hospital. This hospital was meant to provide medical relief for prisoners, who were overworked, sexually abused by guards, tortured, and sometimes killed by prison authorities. Once it was completed, the authorities put prisoners to work cleaning and maintaining it, but the medical infrastructure itself was used to treat those afflicted with venereal diseases in the city at large, not the prisoners who built it—continuing a longstanding strategy of providing social benefits to one section of the working class by intensifying the exploitation of their unemployed and racially targeted neighbors.

The prison was used for the systematic incarceration of loiterers and “drunks,” driven by the moralistic notion that solitude and hard work would renew the “honor” of the captives. Overcrowding, a favorite excuse of the carceral state, was used to justify expanding the prison six times from 1929 to 1960.

In the early 1980s, pressure from the American Civil Liberties Union compelled the Prison Farm to replace its solitary confinement units with twenty additional cells; reformers who do not understand the need to destroy these facilities often consequently function to introduce a more rational and efficient cruelty. Around that time, the sentences for alcoholism and other “quality of life” crimes began to shorten, just as the population of Atlanta began to contract. Between 1970 and 1990, the city lost 21% of its residents—most of them white—as industrial reorganization and racial segmentation in the working class provided jobs for white workers in the clerical, service, and logistics sectors further outside of the city limits, while Black workers remained concentrated in the increasingly destitute and abandoned urban core.

The ruins of the Old Atlanta Prison Farm have long been the haunt of rebels and visionaries.

Do Not Let Them Re-Form

“Carceral reformists hope to use this opportunity to introduce adjustments that will stabilize the regimes of confinement and control for another century. But at this juncture, inspiring actions could catalyze a confrontational movement that pushes for abolition rather than reform.”