Reminiscences of Xelîl, a friend we lost last year.

In October 2012, we organized a lecture tour through Germany on the occasion of the publication of the book Message in a Bottle, a collection of CrimethInc. texts in German. The planning escalated quickly; it became a total of 45 events throughout Northern Europe within less than 2 months.

I was on the road for two weeks of the tour. We did 13 events on 13 days—mostly in Germany, but also in Holland and Belgium. Before the tour, I only knew the other two presenters via mail.

It was an intense tour, full of adventures and meaningful discussions that produced new friendships and connections between communities. Everywhere we went, the venues were full and the conversations went on until late at night. Between events, we visited historic sites, took city tours, climbed onto rooftops, danced at wild parties, and finally hurried to the next event just in time.

On one of those evenings, when we were discussing the basic questions—”What do we mean when we say that we are anarchists? What is our overarching strategy against capitalism?”—I got to know Xelîl, who was going by another name in those days. It was one of the many meaningful encounters on that tour, one of the moments that remained in our memories.

After the discussion, we ended up in an activist collective in which private property was limited to small boxes and which was otherwise based on shared self-organization. We felt at home there immediately.

We sat half the night at the kitchen table. I was drinking wine; I don’t remember if Xelîl drank too. I was impressed by his knowledge of texts from Adorno to Foucault to current CrimethInc. texts and how eagerly and tirelessly he tried to combine the approaches, to find similarities. Reading his obituary in Lower Class Magazine, in which Peter Schaber writes, “He belonged to those people who are constantly driven by the very big questions,” I immediately recalled that encounter.

Xelîl offered to work directly on future translations - and so he became part of the crew that also translated Work. We owe the first 30 pages of the German translation to him.

The introduction describes much of what we discussed that night in 2012:

“At any time, we could all stop paying rent, mortgages, taxes, utilities; they would be powerless against us if we all quit at once. At any time, we could all stop going to work or school—or go to them and refuse to obey orders or leave the premises, instead turning them into community centers. At any time, we could tear up our IDs, take the license plates off our cars, cut down security cameras, burn money, throw away our wallets, and assemble cooperative associations to produce and distribute everything we need.

“Whenever my shift drags, I find myself thinking about this stuff. Am I really the only person who’s ever had this idea? I can imagine all the usual objections, but you can bet if it took off in some part of the world everybody else would get in on it quick. Think of the unspeakable ways we’re all wasting our lives instead. What would it take to get that chain reaction started? Where do I go to meet people who don’t just hate their jobs, but are ready to be done with work once and for all?”

Xelîl on the trail of the revolution in Latin America.

Xelîl’s first band, Unknown Artists.

We stayed in loose contact after working on Work together. Xelîl was one of the first to explain the “new paradigm” of the Kurdish movement to me, inviting me to reconsider my previous concerns about the Kurdish movement and to engage with Abdullah Öcalan’s idea. I remained skeptical, but if I had not been talking with Xelîl and other friends we would not have been able to send Öcalan’s writings and material expressing solidarity with the Kurdish movement to our local bookstore so early. “In a few years, he managed to connect many people and movements with the liberation movement and to build bridges,” proclaims the eulogy published by Internationalist Commune. I can only agree with that.

In 2015, we met again at an information event about the struggle in Kurdistan at which Xelîl reported on his trip to Bakur. After the event, we sat together once again in the living room, talking until early in the morning. There were many things we didn’t agree on, but we were united by the determination to combine struggles and theories, to create something new, to break the mold and depart from the old paths that had led to dead ends. It was an enriching conversation, an example of the sort of respective and productive debating culture that many people wish was more common. When Xelîl polemicized against Western individualism, citing Öcalan, I confronted him with the ideas of Max Stirner; we got into a debate about autonomy, the individual, and the importance of revolutionary politics. Shortly afterwards, we lost contact, but even today, the memory of that night remains clear in my mind.

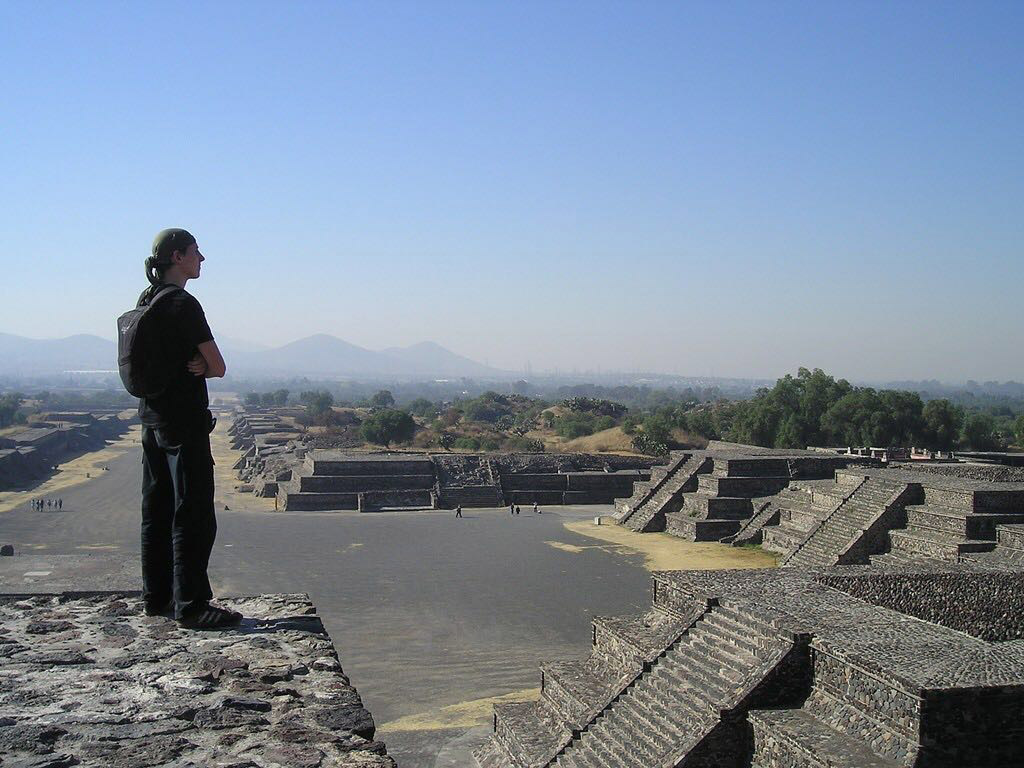

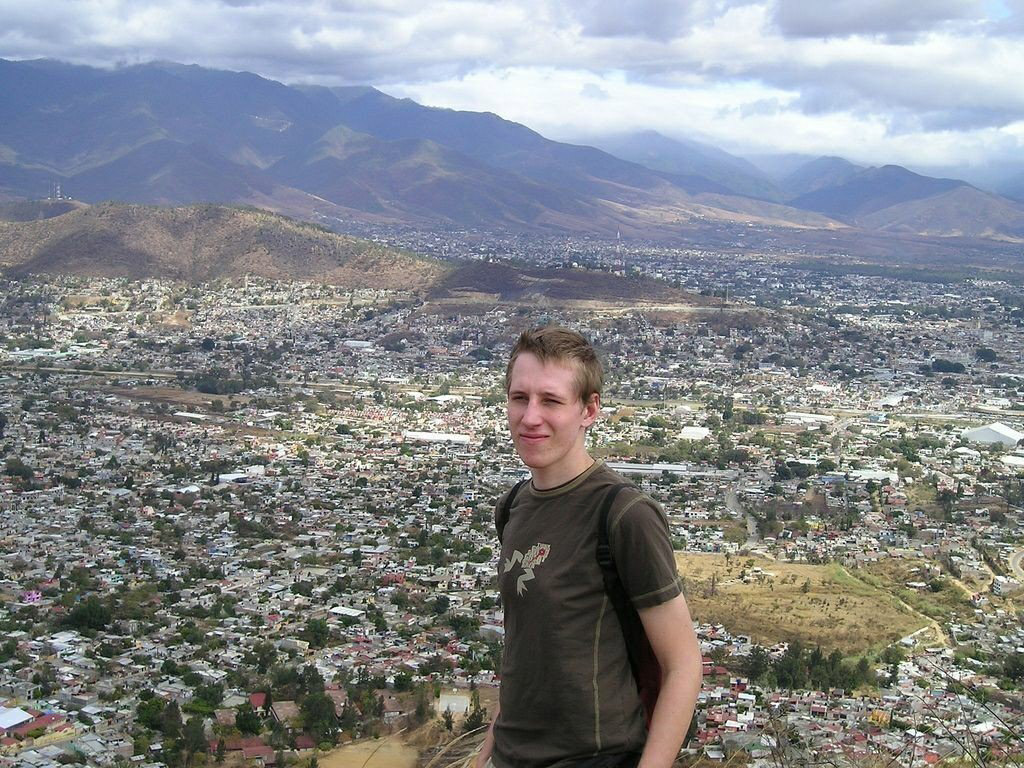

Xelîl traveling in Mexico.

Xelîl visiting Oaxaca, Mexico.

Xelîl in Kurdistan.

Today, I read his text about “revolutionary leadership.” It contains so much that I would like to argue about with him and also some things I would have liked to ask about. “The seeds that Heval Bager has sown on his many travels have begun to germinate and sprout everywhere,” reads the aforementioned eulogy. Hopefully, the seeds he sowed will not only open up in his theory, but also in creating the conditions for discussion and productive struggle.

CrimethInc. published the interview “From Germany to Bakur” in 2015. Xelîl took part in composing the answers. In response to a question about the Kurdish form of struggle, he wrote:

“Let me share a story that a friend once told me. He took part in the Qandil war in 2011. At that time, there was a pragmatic alliance between Turkey and Iran: both had a problem with the Kurdish movement, and were afraid of the military opportunities the guerrillas had. Qandil forms the southern end of the Mediya Defense Territories, the guerrilla-controlled mountains in the border regions of Iran, Iraq, and Turkey. He told me about a situation when one and a half thousand pasdaran, the Iran infantry regiments, tried to storm the hill where the guerrillas were hiding. There were only about thirty comrades defending their mountain. He explained that what the Iranian army tried to use against them were just their bullets, and their fear of punishment from their leaders. They ran blindly upwards, and were defeated. They had no conviction, no energy, no friendship between them. On the other hand, when his comrades defended their position, they didn’t just use their weapons, he told me. They were fighting for their looted villages, for their split families, with their fallen friends in mind, with the consciousness that the attacking army would burn the mountains and forests behind them and destroy the nature in their lands. They fought for those who were too weak to stand alone, for all the parts of society who stood behind them and had their back. Maybe it’s hard to understand if you didn’t feel it yourself. But their energy was backed by a long line of friends, historically experienced oppression, mutual protection—a love for life and a belief in themselves.

“All these things come first, he said, when you’re sitting next to your friends in your guard position and raising your arms in defense: your trust in your comrades, your gratitude for those who believe in a free society living in the valleys, for the ones who cultivate the gardens feeding you, your sadness about the horrors the state did to your friends and families. And in the end, there’s the bullet you shoot at the ones stumbling in your direction. How could they possibly win, he asked, smiling.”

In these lines, we see his admiration and appreciation for the guerrillas in the Mediya defense areas where Xelîl was murdered by the Turkish Air Force in December 2018. He was serving in the ranks of the HPG (Hêzên Parastina Gel, People’s Defense Forces).

In the Kurdish movement, it is said, Şehîd namirin—the dead are immortal. It’s true, martyrs are immortal—but this is true not only of those who died in battle, but also of all who act in search of their full potential, who are seekers on the trail of life, looking for escape routes for all of us out of the global catastrophe that is unfolding today. Xelîl has left behind traces that have made him and his thoughts unforgettable.

Further Reading

The Struggle Is Not for Martyrdom, but for Life