We present this article composed by anarchists in Ukraine to give context for how some participants in social movements there see the difficult events that have played out there over the past nine years. We believe that it is important for people everywhere to grapple with the events they describe below and the questions that those developments pose. This text should be read in the context of the other perspectives we have published from Ukraine and Russia.

This text was composed together by several active anti-authoritarian activists from Ukraine. We do not represent one organization, but we came together to write this text and prepare for a possible war.

Besides us, the text was edited by more than ten people, including participants in the events described in the text, journalists who checked the accuracy of our claims, and anarchists from Russia, Belarus, and Europe. We received many corrections and clarifications in order to write the most objective text possible.

If war breaks out, we do not know if the anti-authoritarian movement will survive, but we will try to do so. In the meantime, this text is an attempt to leave the experience that we have accumulated online.

At the moment, the world is actively discussing a possible war between Russia and Ukraine. We need to clarify that the war between Russia and Ukraine has been going on since 2014.

But first things first.

The Maidan Protests in Kyiv

In 2013, mass protests began in Ukraine, triggered by Berkut (police special forces) beating up student protesters who were dissatisfied with the refusal of then-President Viktor Yanukovych to sign the association agreement with the European Union. This beating functioned as a call to action for many segments of society. It became clear to everyone that Yanukovych had crossed the line. The protests ultimately led to the president fleeing.

In Ukraine, these events are called “The Revolution of Dignity.” The Russian government presents it as a Nazi coup, a US State Department project, and so on. The protesters themselves were a motley crowd: far-right activists with their symbols, liberal leaders talking about European values and European integration, ordinary Ukrainians who went out against the government, a few leftists. Anti-oligarchic sentiments dominated among the protesters, while oligarchs who did not like Yanukovych financed the protest because he, along with his inner circle, tried to monopolize big business during his term. That is to say—for other oligarchs, the protest represented a chance to save their businesses. Also, many representatives of mid-size and small businesses participated in the protest because Yanukovych’s people did not allow them to work freely, demanding money from them. Ordinary people were dissatisfied with the high level of corruption and arbitrary conduct of the police. The nationalists who opposed Yanukovych on the grounds that he was a pro-Russian politician reasserted themselves significantly. Belarusian and Russian expatriates joined protests, perceiving Yanukovych as a friend of Belarusian and Russian dictators Alexander Lukashenko and Vladimir Putin.

If you have seen videos from the Maidan rally, you might have noticed that the degree of violence was high; the protesters had no place to pull back to, so they had to fight to the bitter end. The Berkut wrapped stun grenades with screw nuts that left splinter wounds after the explosion, hitting people in their eyes; that is why there were many injured people. In the final stages of the conflict, the security forces used military weapons—killing 106 protesters.

In response, the protesters produced DIY grenades and explosives and brought firearms to the Maidan. The manufacturing of Molotov cocktails resembled small divisions.

In the 2014 Maidan protests, the authorities used mercenaries (titushkas), gave them weapons, coordinated them, and tried to use them as an organized loyalist force. There were fights with them involving sticks, hammers, and knives.

Contrary to the opinion that the Maidan was a “manipulation by the EU and NATO,” supporters of European integration had called for a peaceful protest, deriding militant protesters as stooges. The EU and the United States criticized the seizures of government buildings. Of course, “pro-Western” forces and organizations participated in the protest, but they did not control the entire protest. Various political forces including the far right actively interfered in the movement and tried to dictate their agenda. They quickly got their bearings and became an organizing force, thanks to the fact that they created the first combat detachments and invited everyone to join them, training and directing them.

However, none of the forces was absolutely dominant. The main trend was that it was a spontaneous protest mobilization directed against the corrupt and unpopular Yanukovych regime. Perhaps the Maidan can be classified as one of the many “stolen revolutions.” The sacrifices and efforts of tens of thousands of ordinary people were usurped by a handful of politicians who made their way to power and control over the economy.

The Role of Anarchists in the Protests of 2014

Despite the fact that anarchists in Ukraine have a long history, during the reign of Stalin, everyone who was connected with the anarchists in any way was repressed and the movement died out, and consequently, the transfer of revolutionary experience ceased. The movement began to recover in the 1980s thanks to the efforts of historians, and in the 2000s it received a big boost due to the development of subcultures and anti-fascism. But in 2014, it was not yet ready for serious historical challenges.

Prior to the beginning of the protests, anarchists were individual activists or scattered in small groups. Few argued that the movement should be organized and revolutionary. Of the well-known organizations that were preparing for such events, there was Makhno Revolutionary Confederation of Anarcho-Syndicalists (RCAS of Makhno), but at the beginning of the riots, it dissolved itself, as the participants could not develop a strategy for the new situation.

The events of the Maidan were like a situation in which the special forces break into your house and you need to take decisive actions, but your arsenal consists only of punk lyrics, veganism, 100-year-old books, and at best, the experience of participating in street anti-fascism and local social conflicts. Consequently, there was a lot of confusion, as people attempted to understand what was happening.

At the time, it was not possible to form a unified vision of the situation. The presence of the far-right in the streets discouraged many anarchists from supporting the protests, as they did not want to stand beside Nazis on the same side of the barricades. This brought a lot of controversy into the movement; some people accused those who did decide to join the protests of fascism.

The anarchists who participated in the protests were dissatisfied with the brutality of the police and with Yanukovych himself and his pro-Russian position. However, they could not have a significant impact on the protests, as they were essentially in the category of outsiders.

In the end, anarchists participated in the Maidan revolution individually and in small groups, mainly in volunteer/non-militant initiatives. After a while, they decided to cooperate and make their own “hundred” (a combat group of 60-100 people). But during the registration of the detachment (a mandatory procedure on the Maidan), the outnumbered anarchists were dispersed by the far-right participants with weapons. The anarchists remained, but no longer attempted to create large organized groups.

Among those killed on the Maidan was the anarchist Sergei Kemsky who was, ironically, ranked as postmortem Hero of Ukraine. He was shot by a sniper during the heated phase of the confrontation with the security forces. During the protests, Sergei put forward an appeal to the protesters entitled “Do you hear it, Maidan?” in which he outlined possible ways of developing the revolution, emphasizing the aspects of direct democracy and social transformation. The text is available in English here.

Gathering of an anarchist squad.

The beginning of the War: The Annexation of Crimea

The armed conflict with Russia began eight years ago on the night of February 26-27, 2014, when the Crimean Parliament building and the Council of Ministers were seized by unknown armed men. They used Russian weapons, uniforms, and equipment but did not have the symbols of the Russian army. Putin did not recognize the fact of the participation of the Russian military in this operation, although he later admitted it personally in the documentary propaganda film “Crimea: The way to the Homeland”.

Armed men in uniforms without insignias blocking a Ukrainian military unit in Crimea on March 9, 2014.

Here, one needs to understand that during the time of Yanukovych, the Ukrainian army was in very poor condition. Knowing that there was a regular Russian army of 220,000 soldiers operating in Crimea, the provisional government of Ukraine did not dare to confront it.

After the occupation, many residents have faced repression that continues to this day. Our comrades are also among the repressed. We can briefly review some of the most high-profile cases. Anarchist Alexander Kolchenko was arrested along with pro-democratic activist Oleg Sentsov and transferred to Russia on May 16, 2014; five years later, they were released as a result of a prisoner exchange. Anarchist Alexei Shestakovich was tortured, suffocated with a plastic bag on his head, beaten, and threatened with reprisals; he managed to escape. Anarchist Evgeny Karakashev was arrested in 2018 for a re-post on Vkontakte (a social network); he remains in custody.

Anarchist Alexander Kolchenko after prisoner exchange.

Disinformation

Pro-Russian rallies were held in Russian-speaking cities close to the Russian border. The participants feared NATO, radical nationalists, and repression targeting the Russian-speaking population. After the collapse of the USSR, many households in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus had family ties, but the events of the Maidan caused a serious split in personal relations. Those who were outside Kyiv and watched Russian TV were convinced that Kyiv had been captured by a Nazi junta and that there were purges of the Russian-speaking population there.

Russia launched a propaganda campaign using the following messaging: “punishers,” i.e., Nazis, are coming from Kyiv to Donetsk, they want to destroy the Russian-speaking population (although Kyiv is also a predominantly Russian-speaking city). In their disinformation statements, the propagandists used photos of the far right and spread all kinds of fake news. During the hostilities, one of the most notorious hoaxes appeared: the so-called crucifixion of a three-year-old boy who was allegedly attached to a tank and dragged along the road. In Russia, this story was broadcasted on federal channels and went viral on the Internet.

Fake news from a Russian channel. A woman tells how she saw the executions and the crucifixion of a three-year-old boy.

In 2014, in our opinion, disinformation played a key role in generating the armed conflict: some residents of Donetsk and Lugansk were scared that they would be killed, so they took up arms and called for Putin’s troops.

Armed Conflict in the East of Ukraine

“The trigger of the war was pulled,” in his own words, by Igor Girkin, a colonel of the FSB (the state security agency, successors to the KGB) of the Russian Federation. Girkin, a supporter of Russian imperialism, decided to radicalize the pro-Russian protests. He crossed the border with an armed group of Russians and (on April 12, 2014) seized the Interior Ministry building in Slavyansk to take possession of weapons. Pro-Russian security forces began to join Girkin. When information about Girkin’s armed groups appeared, Ukraine announced an anti-terrorist operation.

A part of Ukrainian society determined to protect national sovereignty, realizing that the army had poor capacity, organized a large volunteer movement. Those who were somewhat competent in military affairs became instructors or formed volunteer battalions. Some people joined the regular army and volunteer battalions as humanitarian volunteers. They raised funds for weapons, food, ammunition, fuel, transport, renting civil cars, and the like. Often, the participants in the volunteer battalions were armed and equipped better than the soldiers of the state army. These detachments demonstrated a significant level of solidarity and self-organization and actually replaced the state functions of territorial defense, enabling the army (which was poorly equipped at that time) to successfully resist the enemy.

The territories controlled by pro-Russian forces began to shrink rapidly. Then the regular Russian army intervened.

We can highlight three key chronological points:

- The Ukrainian military realized that weapons, volunteers, and military specialists were coming from Russia. Therefore, on July 12, 2014, they began an operation on the Ukrainian-Russian border. However, during the military march, the Ukrainian military was attacked by Russian artillery and the operation failed. The armed forces sustained heavy losses.

- The Ukrainian military attempted to occupy Donetsk. While they were advancing, they were surrounded by Russian regular troops near Ilovaisk. People we know, who were part of one of the volunteer battalions, were also captured. They saw the Russian military firsthand. After three months, they managed to return as the result of an exchange of prisoners of war.

- The Ukrainian army controlled the city of Debaltseve, which had a large railway junction. This disrupted the direct road linking Donetsk and Lugansk. On the eve of the negotiations between Poroshenka (the president of Ukraine at that time) and Putin, which were supposed to begin a long-term ceasefire, Ukrainian positions were attacked by units with the support of Russian troops. The Ukrainian army was again surrounded and sustained heavy losses.

Volunteer fighters carrying out actions in Ilovaisk in 2014.

For the time being (as of February 2022), the parties have agreed on a ceasefire and a conditional “peace and quiet” order, which is maintained, though there are consistent violations. Several people die every month.

Russia denies the presence of regular Russian troops and the supply of weapons to territories uncontrolled by the Ukrainian authorities. The Russian military who were captured claim that they were put on alert for a drill, and only when they arrived at their destination did they realize that they were in the middle of the war in Ukraine. Before crossing the border, they removed the symbols of the Russian army, the way their colleagues did in Crimea. In Russia, journalists have found cemeteries of fallen soldiers, but all information about their deaths is unknown: the epitaphs on the headstones only indicate the dates of their deaths as the year 2014.

Supporters of the Unrecognized Republics

The ideological basis of the opponents of the Maidan was also diverse. The main unifying ideas were discontent with violence against the police and opposition to rioting in Kyiv. People who were brought up with Russian cultural narratives, movies, and music were afraid of the destruction of the Russian language. Supporters of the USSR and admirers of its victory in World War II believed that Ukraine should be aligned with Russia and were unhappy with the rise of radical nationalists. Adherents of the Russian Empire perceived the Maidan protests as a threat to the territory of the Russian Empire. The ideas of these allies could be explained with this photo showing the flags of the USSR, the Russian Empire, and the St. George ribbon as a symbol of victory in the Second World War. We could portray them as authoritarian conservatives, supporters of the old order.

The flags of the USSR, the Russian Empire, and the St. George ribbon as a symbol of victory in the Second World War.

The pro-Russian side consisted of police, entrepreneurs, politicians, and the military who sympathized with Russia, ordinary citizens frightened by fake news, various ultra-right indivisuals including Russian patriots and various types of monarchists, pro-Russian imperialists, the Task Force group “Rusich,” the PMC [Private Military Company] group “Wagner,” including the notorious neo-Nazi Alexei Milchakov, the recently deceased Egor Prosvirnin, the founder of the chauvinistic Russian nationalist media project “Sputnik and Pogrom,” and many others. There were also authoritarian leftists, who celebrate the USSR and its victory in the Second World War.

The Rise of the Far Right in Ukraine

As we described, the right wing managed to gain sympathy during the Maidan by organizing combat units and by being ready to physically confront the Berkut. The presence of military arms enabled them to maintain their independence and force others to reckon with them. In spite of their using overt fascist symbols such as swastikas, wolf hooks, Celtic crosses, and SS logos, it was difficult to discredit them, as the need to fight the forces of the Yanukovych government caused many Ukrainians to call for cooperation with them.

After the Maidan, the right wing actively suppressed the rallies of pro-Russian forces. At the beginning of the military operations, they started forming volunteer battalions. One of the most famous is the “Azov” battalion. At the beginning, it consisted of 70 fighters; now it is a regiment of 800 people with its own armored vehicles, artillery, tank company, and a separate project in accordance with NATO standards, the sergeant school. The Azov battalion is one of the most combat-effective units in the Ukrainian army. There were also other fascist military formations such as the Volunteer Ukrainian Unit “Right Sector” and the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, but they are less widely known.

As a consequence, the Ukrainian right wing accrued a bad reputation in the Russian media. But many in Ukraine considered what was hated in Russia to be a symbol of struggle in Ukraine. For example, the name of the nationalist Stepan Bandera, who is known chiefly as a Nazi collaborator in Russia, was actively used by the protesters as a form of mockery. Some called themselves Judeo-Banderans to troll supporters of Jewish/Masonic conspiracy theories.

Over time, the trolling contributed to a rise in far-right activity. Right-wingers openly wore Nazi symbols; ordinary supporters of the Maidan claimed that they were themselves Banderans who eat Russian babies and made memes to that effect. The far right made its way into the mainstream: they were invited to participate in television shows and other corporate media platforms, on which they were presented as patriots and nationalists. Liberal supporters of the Maidan took their side, believing that the Nazis were a hoax invented by Russian media. In 2014 to 2016, anyone who was ready to fight was embraced, whether it was a Nazi, an anarchist, a kingpin from an organized crime syndicate, or a politician who did not carry out any of his promises.

Far-right fighters with a swastika and a NATO flag. The Azov battalion has a negative attitude towards NATO; currently, the US does not transfer weapons to Azov.

The rise of the far right is due to the fact that they were better organized in critical situations and were able to suggest effective methods of fighting to other rebels. Anarchists provided something similar in Belarus, where they also managed to gain the sympathy of the public, but not on as significant of a scale as the far right did in Ukraine.

By 2017, after the ceasefire started and the need for radical fighters decreased, the SBU (Security Service of Ukraine) and the state government co-opted the right-wing movement, jailing or neutralizing anyone who had an “anti-system” or independent perspective on how to develop the right-wing movement—including Oleksandr Muzychko, Oleg Muzhchil, Yaroslav Babich, and others.

Today, it is still a big movement, but their popularity is at a comparably low level and their leaders are affiliated with the Security service, police, and politicians; they do not represent a really independent political force. The discussions of the problem of the far-right are becoming more frequent within the democratic camp, where people are developing an understanding of the symbols and organizations they are dealing with, rather than silently dismissing concerns.

Ukrajinští anarchisté analyzují vývoj hnutí a jeho možnosti tváří v tvář hrozbě války s Ruskem

S vypuknutím bojů na Donbase se v roce 2014 antifašistická a částečně i anarchistická scéna rozdělila na ty, kdo podporují svrchovanost Ukrajiny, a ty, kteří stojí za takzvanými lidovými republikami (Doněckou lidovou republikou – DNR a Luhanskou lidovou republikou – LNR), samozvanými státními útvary, jež za ruské podpory vedou vleklý boj s ukrajinskou armádou.

V prvních měsících války se na alternativní a punkové scéně rozšířil postoj „říci válce ne“, ten však neměl dlouhého trvání. Dynamika situace vtáhla mnoho aktivistů a vedla k vytvoření poměrně stabilního proukrajinského a proruského tábora. Ty nyní zanalyzujeme.

Proukrajinský tábor

Někteří z hnutí se rozhodli aktivně zapojit do probíhajícího konfliktu na straně Ukrajiny. Vzhledem k absenci masové organizace odcházeli první anarchističtí a antifašističtí dobrovolníci do války na Donbase jako jednotlivci, vojenští medici a další dobrovolníci. Pokusili se vytvořit vlastní oddíl, ale kvůli nedostatku znalostí a prostředků neúspěšně. Jsou antifašisté, kteří se dokonce připojili k ultrapravicovému batalionu Azov [mezinárodní pluk, který se zapojil do řady vojenských operací; přinejmenším část bojovníků jsou prokazatelně neonacisté – oddíl má ostatně ve znaku wolfsangel, nacistický symbol; Úřad komisaře pro lidská práva OSN spojuje Azov s válečnými zločiny včetně drancování, mučení a znásilňování – pozn. překl.] a k OUN (Organizaci ukrajinských nacionalistů). Důvody byly prozaické: šlo o nejdostupnější jednotky. V důsledku někteří konvertovali k pravicové politice.

[Editors’ note: Although we do not know the details of these events—and it is difficult to confirm them while the authors are in the midst of a full-scale war—obviously any supposed anti-fascist or “anarchist” who joined a fascist-organized militia was never really an anarchist in the first place. We preserve this paragraph as it arrived because we believe it is important to be critical and to center the voices of people in the midst of the events. You can read more of our thoughts about it here.]

- Anti-fascists receiving training at the Right Sector base in Desna. It is worth noting that this photo includes two Moscow anti-fascists who joined the armed conflict.

Lidé neúčastnící se bojů shromažďovali finanční prostředky na zotavení zraněných z Donbasu či na stavbu protiatomového krytu v mateřské škole poblíž frontové linie. V Charkově také existoval squat Autonomie, otevřené anarchistické sociální a kulturní centrum; v té době se soustředil na pomoc uprchlíkům z východu. Zajišťoval bydlení, vzdělávací aktivity a stálý freeshop, sloužil jako informační bod pro nově příchozí. Kromě toho se stal místem teoretických diskusí. Žel v roce 2018 zanikl.

Podobné akce byly individuální iniciativou konkrétních lidí a skupin, neděly se v rámci jednotné strategie.

Jedním z nejvýznamnějších fenoménů byla dříve velká radikální nacionalistická organizace Autonomnij Opir (Autonomní odpor, AO). V roce 2012 se začala přiklánět k levici, do roku 2014 se posunula natolik, že se jednotliví členové dokonce označovali za „anarchisty“. Tito aktivisté svůj nacionalismus rámovali jako boj za „svobodu“ a protiváhu nacionalismu ruskému, za vzor si brali zapatistické hnutí a Kurdy. Ve srovnání s ostatními organizacemi byli anarchisty vnímáni jako nejbližší spojenci, takže s nimi někteří spolupracovali, zatímco jiní takovou spolupráci i AO samotný kritizovali. Členové AO se aktivně účastnili dobrovolnických praporů a snažili se mezi vojáky rozvíjet myšlenku „antiimperialismu“. Hájili právo žen na účast ve válce, členky AO se podílely na bojových operacích. AO pomáhal výcvikovým střediskům v přípravě bojovníků a mediků, dobrovolně se hlásil do armády a organizoval sociální centrum Citadela ve Lvově, kde byli ubytováni uprchlíci.

Moscow, 2014: Anarchists marching against Russian aggression.

Prorusky orientované síly

Moderní ruský imperialismus je postaven na představě, že Rusko je nástupcem SSSR – nikoliv jako politického systému, ale na územním základě. Putinův režim vnímá sovětské vítězství ve druhé světové válce nikoli jako ideologický triumf nad nacismem, ale jako vítězství nad Evropou, které ukazuje sílu Ruska. V Rusku a jím ovládaných zemích má obyvatelstvo menší přístup k informacím, takže Putinova propagandistická mašinerie se neobtěžuje vytvářet komplexní politickou koncepci. Narativ je v podstatě následující: Rusko je nástupcem SSSR a celé území bývalého SSSR je ruské. Sovětské tanky vjely do Berlína, což znamená, že „to zvládneme znovu“ a ukážeme NATO, kdo je tady pánem. Důvodem, proč se Evropa „rozkládá“, je to, že se tam vymkli kontrole všichni ti homosexuálové a imigranti.

Very popular stickers in Russia in 2014 and 2015. The inscription reads “We can do it again.”

Ideologickým základem udržujícím proruský postoj levice bylo tedy dědictví SSSR a vítězství ve druhé světové válce. Protože Rusko tvrdí, že se vlády v Kyjevě zmocnili nacisté a junta, označovali se odpůrci Majdanu za bojovníky proti fašismu a kyjevské juntě. Tato rétorika vyvolala sympatie autoritářské levice – na Ukrajině například organizace Borotba. Během nejvýznamnějších událostí roku 2014 zaujala nejprve vlastenecký, později proruský postoj. Několik jejích aktivistů bylo zabito při nepokojích v Oděse [brutální a chaotické střety pro- a protimajdanských sil kulminující 2. května 2014, kdy bylo zastřeleno šest lidí a desítky dalších vážně zraněny; konflikt vyvrcholil zatlačením proruské strany do budovy, která následně (zřejmě kvůli házení molotovů z obou stran) vzplála a 42 osob zde zahynulo – pozn. překl.]. Část skupiny se také účastnila bojů v Doněcké a Luhanské oblasti, někteří aktivisté tam zahynuli.

Členové Borotby popisovali svou motivaci jako boj proti fašismu. Vyzvali evropskou levici, aby solidarizovala s DNR a LNR. Poté co byl hacknut e-mail Putinova politického stratéga Vladislava Surkova, vyšlo najevo, že aktivisté z Ruska obdrželi finanční prostředky a byli pod dohledem Surkovových lidí.

Ruští autoritářští komunisté se separatistickým republikám věnovali z podobných důvodů.

Apolitické antifašisty k podpoře DNR a LNR motivovala přítomnost krajní pravice na Majdanu. I část z nich se účastnila bojů v Doněcké a Luhanské oblasti, někteří tam padli.

Mezi ukrajinskými antifašisty se nacházeli i „apolitičtí“ antifašisté: subkulturně spříznění lidé, kteří měli negativní vztah k fašismu, „protože proti němu bojovali naši dědové“. Jejich chápání tématu se neslo v abstraktní rovině, sami byli často politicky nesoudržní, sexističtí, homofobní, s vlasteneckými city k Rusku a podobně.

Myšlenka podpory samozvaných republik získala v Evropě širokou podporu mezi levicí. Nejvýznamnějšími stoupenci se stala italská ska-punková kapela Banda Bassotti a německá strana Die Linke. Kromě shromažďování finančních prostředků podnikla Banda Bassotti turné do „Novoruska“. Die Linke, přítomná v Evropském parlamentu, všemožně podporovala proruský narativ a pořádala videokonference s proruskými bojovníky, jezdila na Krym a do neuznaných republik. Mladší členové Die Linke, stejně jako stranická Nadace Rosy Luxemburgové tvrdí, že postoj nesdílí všichni partajníci, ale zjevně jej zastávají nejvýznamnější členové strany, jako je Sahra Wagenknechtová a Sevim Dağdelen.

Banda Bassotti in Donetsk in 2014.

Mezi anarchisty si proruský postoj popularitu nezískal. Z jednotlivých prohlášení byl nejviditelnější postoj Jeffa Monsona, bojovníka MMA z USA, který má tetování s anarchistickými symboly. Dříve se považoval za anarchistu, ale v Rusku otevřeně pracuje pro vládnoucí stranu Jednotné Rusko a je poslancem Dumy.

Shrneme-li proruský levicový tábor, vidíme práci ruských zvláštních služeb a důsledky ideologické neschopnosti. Ukázkou je, jak po okupaci Krymu oslovili pracovníci ruské FSB [Federální služba bezpečnosti navazující na sovětskou KGB, hlavní domácí „protiteroristická“ kontrarozvědka zabývající se mimo jiné šikanou opozice – pozn. překl.] místní antifašisty a anarchisty a nabídli, že jim umožní pokračovat v činnosti, pokud budou napříště propagovat myšlenku, podle níž má být Krym součástí Ruska. Na Ukrajině existují malé informační a aktivistické skupiny vydávající se za antifašisty, vyjadřující ale hlavně proruské postoje. Mnoho lidí je podezřívá, že pro Rusko pracují. Jejich vliv je minimální, ale dotyční slouží ruským propagandistům jako ti, co „autenticky“ upozorňují na nešvary Ukrajiny.

Existují také nabídky „spolupráce“ ze strany ruského velvyslanectví a proruských poslanců, jako je Ilja Kiva. Snaží se hrát na negativní postoj k nacistům typu praporu Azov a snaží se aktivisty uplácet. V současné době se k takovému přijímání peněz otevřeně přiznala pouze Rita Bondar. Dříve psala pro levicová a anarchistická média, ale kvůli potřebě financí psala pod pseudonymem pro mediální platformy spojené s ruským propagandistou Dmitrijem Kiselevem.

V samotném Rusku jsme svědky likvidace anarchistického hnutí a nástupu autoritářských komunistů, kteří vytlačují anarchisty z antifašistické subkultury. Jedním z nejpříznačnějších momentů poslední doby je loňské uspořádání antifašistického turnaje na památku „sovětského vojáka“.

Anarchistický postoj k otevřené válce s Ruskem

Ještě před deseti lety by se myšlenka na plnohodnotnou válku v Evropě zdála šílená, protože si sekulární evropské státy jednadvacátého století hrají na „humanismus“ a své zločiny maskují. To, co nyní mění situaci, je Rusko. Byli jsme svědky okupace Krymu a následných zfalšovaných referend, války na Donbase a sestřelení letadla MH17. Ukrajina neustále zažívá hackerské útoky a bombové hrozby, a to nejen ve státních budovách, ale i uvnitř škol a školek.

V Bělorusku se proruský diktátor Lukašenko v roce 2020 drze prohlásil za vítěze zmanipulovaných voleb. Následné povstání naštvané, prodemokraticky naladěné společnosti, jím otřáslo. Situaci změnilo přistání letadel ruské FSB, běloruské vládě se podařilo protesty násilně potlačit.

Podobný scénář se odehrál v Kazachstánu: režimem otřásly prudké lidové protesty, v rámci Organizace smlouvy o kolektivní bezpečnosti ale přijely armády Ruska, Běloruska, Arménie a Kyrgyzstánu poskytnout „bratrskou pomoc“, aby povstání, již tak zasažené tvrdou represí, dorazily.

Ruské speciální služby vylákaly uprchlíky ze Sýrie do Běloruska, aby vyvolaly konflikt na hranicích s Evropskou unií. Byla také odhalena skupina FSB, která se zabývala politickými vraždami za použití známého „novičoku“. Kromě Skripalových a Navalného zabíjeli v Rusku i další politické osobnosti. Putinův režim na všechna obvinění reaguje slovy: „My za to nemůžeme, všichni lžete.“ Současně se snaží, aby se obvinění nepotvrdila. Mezitím sám Putin před půl rokem napsal text, v němž tvrdí, že Rusové a Ukrajinci jsou jeden národ a měli by být spolu. Vladislav Surkov (politický stratég ruské státní politiky spojený s vládami loutkových republik na Donbase) zveřejnil článek, kde prohlásil, že „impérium se musí rozšířit, jinak zanikne“.

Když to vezmeme kolem a kolem, pravděpodobnost plnohodnotné války je teď vysoká – letos ještě o něco vyšší než loni. A ani ti nejbystřejší analytici pravděpodobně nebudou schopni předpovědět, kdy přesně začne. Napětí v regionu by možná zmírnila revoluce v Rusku, jak jsme však psali výše, tamní protestní hnutí bylo zadušeno.

Anarchisté na Ukrajině, v Bělorusku a v Rusku většinově přímo nebo nepřímo podporují ukrajinskou nezávislost. Je to proto, že i přes veškerou nacionální hysterii, korupci a velký počet nacistů vypadá Ukrajina ve srovnání s Ruskem a jím ovládanými zeměmi jako ostrov svobody. Země si zachovává takové – na poměry postsovětského regionu tak unikátní – výdobytky, jako je možnost vyměnit prezidenta, parlament s větší než nominální mocí a právo na pokojné shromažďování. V některých případech, byť podle toho, jak moc dává veřejnost pozor, fungují soudy podle pravidel. Neřekneme nic nového, když konstatujeme, že ve srovnání s Ruskem je nám lépe. Jak napsal Bakunin: „Jsme pevně přesvědčeni, že i ta nejnedokonalejší republika je tisíckrát lepší než nejosvícenější monarchie.“

Ukrajina má mnoho problémů, ale ty se spíše vyřeší bez zásahu Ruska než s ním.

Máme tedy v případě invaze bojovat s ruskými vojsky? Domníváme se, že odpověď zní ano. Mezi možnosti, které ukrajinští anarchisté v současné době zvažují, patří vstup do ozbrojených sil Ukrajiny, zapojení do teritoriální obrany [místně formované dobrovolnické oddíly, které mají teoreticky sloužit k boji s menšími útvary nepřítele, jako jsou výsadky a sabotérská komanda, pozn. překl.], partyzánství a dobrovolnictví.

Ukrajina je nyní v čele boje proti ruskému imperialismu. Ten má dlouhodobé plány na zničení demokracie v Evropě. Víme, že tomuto nebezpečí je zatím věnována malá pozornost. Pokud však sledujete výroky vysoce postavených politiků, krajně pravicových organizací a autoritářských komunistů, časem zjistíte, že v Evropě již existuje rozsáhlá špionážní a kolaborační síť. Například někteří vrcholní představitelé po odchodu z funkce získávají místo v ruské ropné společnosti (Gerhard Schröder, François Fillon).

Hesla „Řekni ne válce!“ nebo „Je to jen válka impérií, USA a Ruska“ považujeme za neúčinná a populistická. Anarchistické hnutí nemá na proces, kterým se konflikt zrodil a probíhá, žádný vliv, podobná prohlášení prostě nic nezmění.

Náš postoj vychází z toho, že nechceme utíkat, nechceme být rukojmími a nechceme se nechat zabít bez boje. Stačí se podívat na Afghánistán a pochopíte, co může znamenat „ne válce“: když Tálibán zvítězil, lidé hromadně prchali, umírali v chaosu na letišti a ty, kteří zůstali, zasáhly čistky. To se děje i na Krymu – a můžete si představit, co se bude dít po invazi Ruska v dalších oblastech Ukrajiny.

Afghanistan, 2021: People try to get on a NATO plane to escape the Taliban.

Co se týče postoje k NATO, autoři tohoto textu se dělí podle postoje. Někteří z nás mají v dané situaci k alianci pozitivní přístup. Je zřejmé, že Ukrajina nemůže Rusku čelit sama. I když zohledníme velké počty dobrovolníků, jsou zapotřebí moderní technologie a zbraně. Kromě NATO nemá Ukrajina žádné spojence, kteří by jí s tím mohli pomoci.

Zde můžeme připomenout příběh syrského Kurdistánu, Rojavy. Místní obyvatelé byli nuceni spolupracovat s NATO proti takzvanému Islámskému státu, jedinou alternativou byl útěk nebo smrt. I díky tomuto případu ale dobře víme, že podpora ze strany NATO může velmi rychle zmizet, pokud Západ získá nové zájmy nebo se mu podaří vyjednat s Putinem nějaké kompromisy.

Případná ruská invaze zkrátka nutí Ukrajince hledat spojence. Ne na sociálních sítích, ale v reálném světě. Anarchisté nemají na Ukrajině ani jinde dostatek prostředků, aby mohli účinně reagovat na invazi Putinova režimu. Proto je třeba uvažovat o přijetí podpory od NATO.

Na druhou stranu je část autorů toho názoru, že NATO i EU posílením svého vlivu na Ukrajině upevní současný systém divokého kapitalismu a dále zhorší možnosti sociální revoluce. V systému globálního kapitalismu, jehož vlajkovou lodí jsou USA jako vůdce NATO, je Ukrajině přisouzeno místo skromného pohraničníka: dodavatele levné pracovní síly a zdrojů. V této perspektivě je důležité, aby si ukrajinská společnost uvědomila potřebu nezávislosti na všech imperialistech. V souvislosti s obranyschopností země by se neměl klást důraz na význam techniky NATO a podporu pravidelné armády, ale potenciál společnosti pro partyzánský odpor zdola.

Válku považujeme především za válku proti Putinovi a jím ovládaným režimům. Kromě prozaické motivace nežít pod diktaturou vidíme potenciál v ukrajinské společnosti, která je jednou z nejaktivnějších, nejnezávislejších a nejvzpurnějších v regionu. Dlouhá historie odporu obyvatelstva za posledních třicet let je toho pádným důkazem. To dává naději, že u nás mají živnou půdu koncepty přímé demokracie.

Současná situace anarchistů a nové výzvy

Naše postavení outsidera během Majdanu i války mělo na hnutí demoralizující vliv. Osvětová činnost byla ztížena, protože ruská propaganda si monopolizovala slovo „antifašismus“. Vzhledem k přítomnosti symbolů SSSR mezi proruskými bojovníky byl postoj ke slovu „komunismus“ krajně negativní, takže i spojení „anarchokomunismus“ se vnímalo negativně. Stín pochybnosti na anarchisty vrhala v očích obyčejných lidí i prohlášení proti proukrajinské ultrapravici. Existovala tu nevyřčená dohoda, že fašisté nebudou útočit na anarchisty a antifašisty, pokud nebudeme vystavovat své symboly na shromážděních a podobně. A pravice měla v rukou spoustu zbraní, situace vyvolávala pocit frustrace. Policie pořádně nefungovala, takže mohl být leckdo bez následků snadno zabit. Například v roce 2015 byl zastřelen proruský aktivista Oles Buzina [otevřeně proruský publicista angažující se dlouhé roky v nejrůznějších veřejných kauzách – deklarativně antifašista, ale kritizován za sexismus a homofobii; podezření za vraždu padlo na ukrajinskou ultrapravici – pozn. překl.].

To vše povzbudilo anarchisty, aby k věci přistupovali vážněji.

Od roku 2016 se rozvíjel radikální underground. Radikálnější anarchistické zdroje vysvětlovaly, jak si pořídit zbraně a zakládat skrýše – v minulosti přitom zmiňovaly maximálně Molotovovy koktejly.

V anarchistickém prostředí se stalo přijatelným mít legální zbraně, začala se objevovat videa z anarchistických výcvikových táborů.

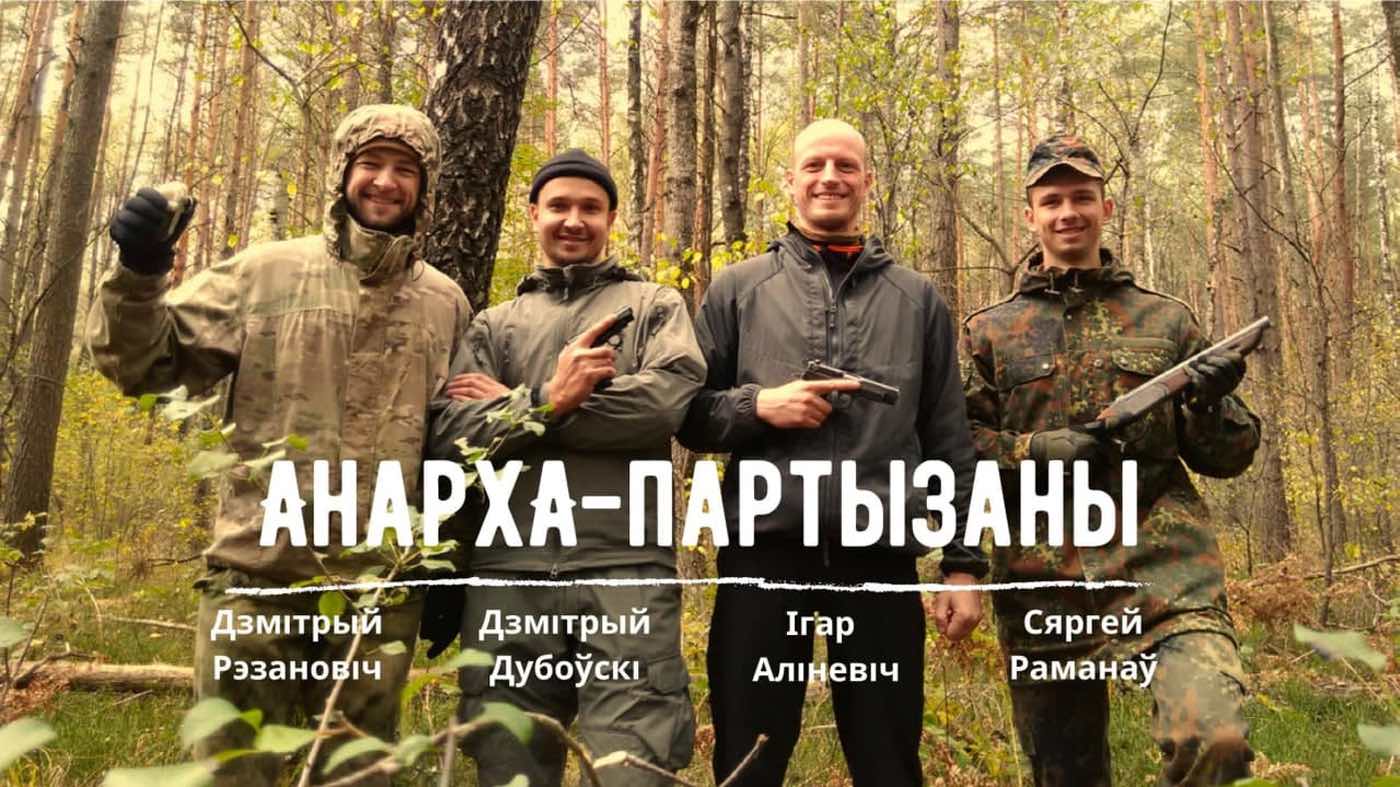

Dozvuky těchto změn zasáhly Rusko a Bělorusko. V Rusku FSB zlikvidovala síť anarchistických skupin, které měly legální zbraně a cvičily airsoft. Zatčené mučili elektrickým proudem, aby se přiznali k „terorismu“, výsledkem byly tresty od 6 do 18 let vězení. V Bělorusku byla při pokusu o překročení hranice z Ukrajiny zadržena skupina anarchopartyzánů vystupující pod názvem Černý prapor. Měli u sebe střelnou zbraň a granát; jeden ze zatčených, Igor Olinevič [v kauze s tím spojené byl v Bělorusku odsouzen na 20 let vězení – pozn. překl.], uvedl, že si zbraň koupil v Kyjevě.

Anarchist rebel group “Black Flag”

Změnil se také zastaralý přístup anarchistů k ekonomické agendě: jestliže dříve většina pracovala na špatně placených místech „blíže utlačovaným“, nyní se mnozí snaží najít práci s dobrým platem, nejčastěji v IT sektoru.

Pouliční antifašistické skupiny obnovily činnost a zapojily se do odvetných akcí proti neonacistickým útokům. Mimo jiné uspořádaly antifašistický turnaj bojových umění „No Surrender“, natočily dokumentární film s názvem Hoods, který vypráví o zrodu kyjevské Antify. Anarchisté se také věnují monitoringu ultrapravice.

Antifašismus nabyl důležitosti i proto, že k již tak velkému počtu místních ultrapravicových aktivistů sem přibylo i mnoho známých neonacistů z Ruska (Sergej Korotkič, Alexej Levkin), zbytku Evropy (Denis „White Rex“ Kapustin), a dokonce z USA (Robert Rando).

I v takových podmínkách existují aktivistické skupiny různého druhu (klasičtí anarchisté, queer anarchisté, anarchofeministky, Food Not Bombs, ekoiniciativy a podobně), stejně jako malé informační platformy. Nedávno se objevil politicky nabitý antifašistický zdroj na Telegramu, @uantifa.

Dřívější napětí mezi jednotlivými skupinami postupně vyprchává, probíhá mnoho společných akcí a jednotná účast na sociálních konfliktech. Mezi největší z nich patří kampaň proti deportaci běloruského anarchisty Alexeje Bolenkova (kterému se podařilo vyhrát soud s ukrajinskými speciálními službami a zůstat na Ukrajině) a obrana jedné z kyjevských čtvrtí (Podil) před policejními nájezdy a útoky ultrapravice.

Na společnost jako celek máme stále velmi malý vliv. Je to do značné míry proto, že samotná myšlenka organizovaných anarchistických struktur byla dlouho ignorována nebo popírána – na tento nedostatek si ve svých pamětech ostatně stěžoval už Nestor Machno. Anarchistické skupiny byly v minulosti velmi rychle rozmetány SBU (Bezpečnostní službou Ukrajiny) nebo krajní pravicí.

Nyní jsme se dostali ze stagnace a rozvíjíme se, a proto očekáváme nové represe a nové pokusy SBU o kontrolu hnutí.

Naši roli lze v tuto chvíli označit jako vytváření nejradikálnějšího křídla demokratického tábora. Zatímco si liberálové jdou v případě útoku ultrapravice nebo policie stěžovat té samé policii, anarchisté raději nabízejí v podobných situacích ostatním skupinám spolupráci a přicházejí bránit místa a akce, kde útok hrozí.

Snažíme se vytvářet horizontální vazby ve společných zájmech tak, aby komunity mohly řešit vlastní potřeby včetně sebeobrany. Tím se výrazně lišíme od běžné ukrajinské politické praxe, kde je obvyklé se sdružovat kolem centrálních organizací, lídrů nebo policie – a tyto organizace či vůdci jsou často podplaceni a jejich následovníci oklamáni. Policie může například chránit akce LGBTQ+ komunity, ale rozzlobí se, pokud se tito lidé připojí ke vzpouře proti policejní brutalitě. Vlastně právě proto vidíme v našich myšlenkách potenciál – ale pokud vypukne válka, hlavní bude znovu schopnost účastnit se ozbrojeného konfliktu.

For further reading, you could start with Anarchist Fighter’s response to this article.