The rapid response networks people organized to defend their communities against federal agents seeking to kidnap, brutalize, and terrorize them have undergone a whirlwind evolution to keep up with ever-shifting Immigration and Customs Enforcement tactics. Over the past month and a half of occupation, volunteers in the Twin Cities have continuously updated their rapid response model, arriving at a dynamic and resilient system. In the following report, we explore the details of that system for the benefit of others around the country who may soon be facing similar pressures.

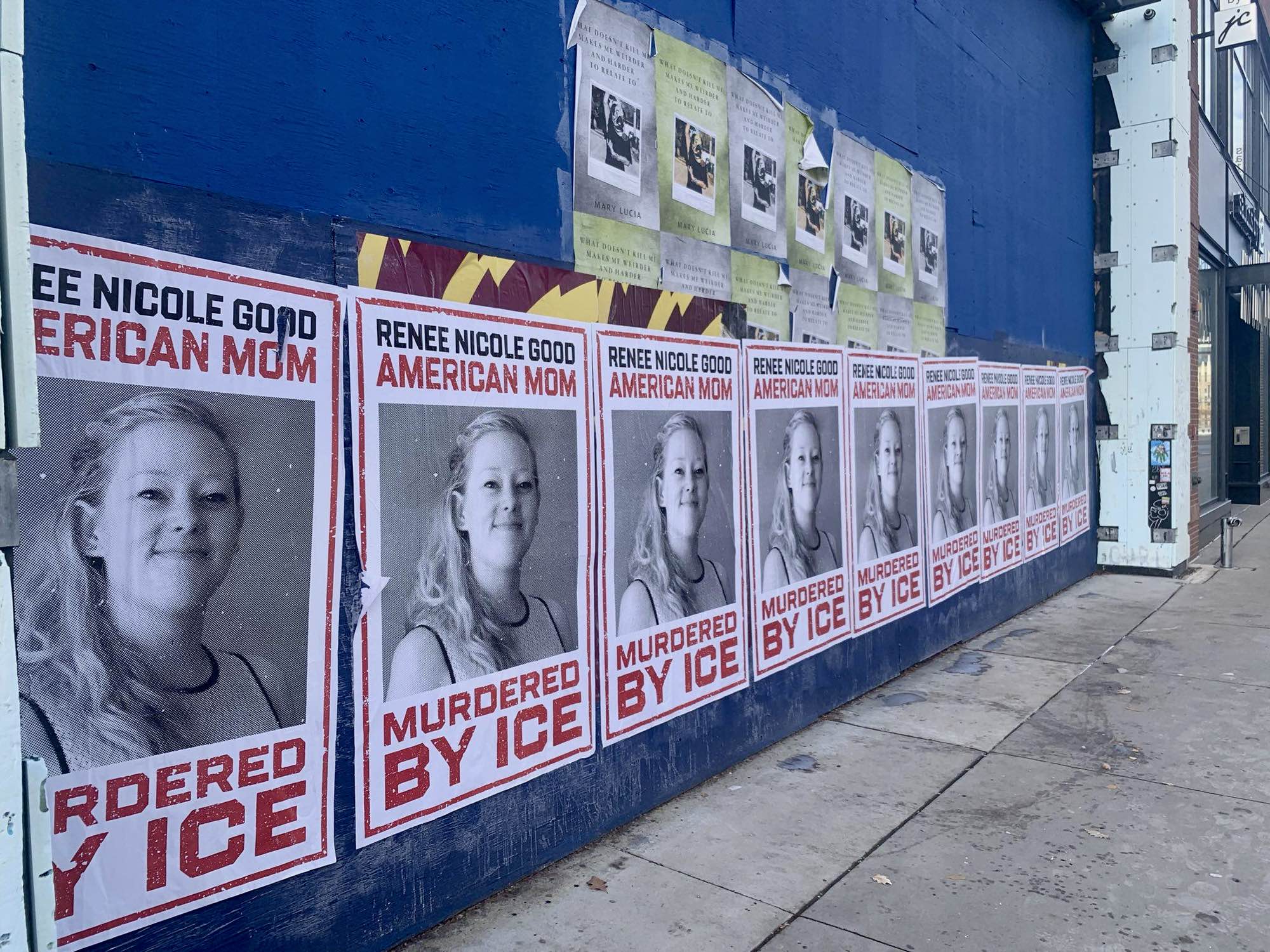

On December 2, 100 Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents were deployed to the Twin Cities as part of a multi-city surge in detentions and deportations. Since then, the Twin Cities have become cities under siege, unrecognizable to many residents. The number of federal officers occupying them has jumped 30-fold to nearly 3000. For comparison, the Minneapolis Police Department has roughly 600 officers. The murder of Renee Nicole Good, a member of the rapid response network, on January 7, followed a week later by the shooting of another person on January 14, has caught the attention of the nation.

Nonetheless, most people assume that what is happening in the Twin Cities looks like ICE enforcement and resistance in other parts of the country. On the contrary, the scale of detentions, deportations, and clashes is without precedent.

To learn about the earlier iteration of the rapid response model, developed in Los Angeles and refined in Chicago and elsewhere over the fall, start here. To learn how to set up admin-only Signal loops, start here.

The Surge

During the months preceding the surge of ICE agents to the Twin Cities, local people and organizations created a relatively centralized rapid response network, in which observers would submit sightings with varying levels of substantiation to an admin on a mass text system. As soon as admins could intake, reformat, and verify the reports, they would blast it out on the system and people nearby would converge. This seemed to work for turning people out to major operations, like a raid on an apartment complex, but began to falter as ICE experimented with faster, more lightweight operations.

Then, around December 1, the raids essentially stopped, and the influx of agents began a campaign of door knocks and snatch-and-grabs. The previous model was immediately rendered obsolete, because the window of time to intervene shrank to a matter of minutes. Community members who were wanting something more confrontational than the existing legal-observer-style bottle-necked system started to build out a parallel system to fill the gaps and move more nimbly.

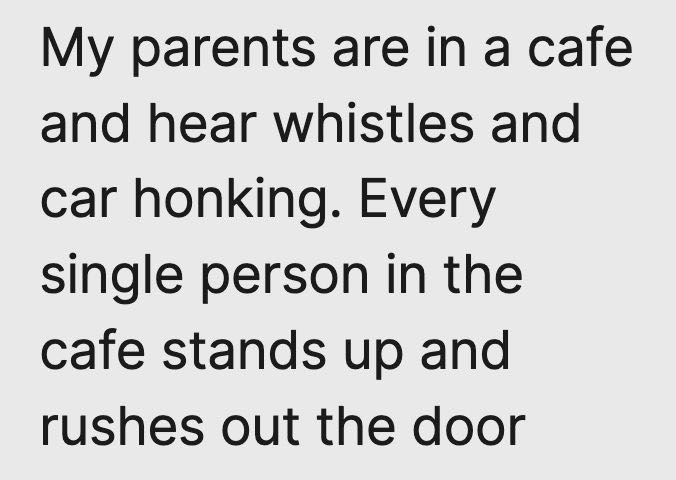

This new system began with a large-scale chat for Southside reports, where anyone can drop an alert of any kind. As ICE operations accelerated in volume and speed, the open, more nimble chat grew in members and became a space that attracted those who wanted to do more than simply record ICE operations. People integrated the existing whistle program to alert targeted people about ICE’s arrival and to harass the agents, then increasingly got in the way—blocking ICE vehicles with personal cars, using their bodies to block agents, using crowds and car patrols to intimidate small groups of agents into withdrawing.

As the chats got larger, more chats were made to break the city up into smaller and smaller segments—some of which have gotten as small as a four-block radius. This allows people to see reports directly relevant to them and respond to nearby sightings quickly and effectively.

Counter-Surveillance

These networks have benefited greatly from a program of counter-surveillance at the local ICE headquarters. The Whipple, a federal building in Fort Snelling on the outskirts of the Minneapolis and St. Paul, has long been a regional headquarters for ICE, having previously housed other federal agencies. The complex is located across the street from a National Guard base, down the road from a military base, and next to the preserved fort itself. The fort sits on the sacred site of the convergence of two rivers. It was one of the earliest sites of colonization in the area; at one time, it was a concentration camp holding native Dakota people.

The Whipple includes offices, processing and detention facilities in the basement, and a sprawling parking lot. Community members identified this complex as a key location over the summer; they have maintained a presence there since August.

The building is hemmed in by two state highways, two rivers, and an airport. With only two vehicle exits, tracking ICE vehicles entering and exiting the facility is easy. Whipple Watch, as it’s called, has involved protesters and observers stationed there for months, gathering intel on the convoys headed into the city or taking detainees to the airport, identifying patterns of operations such as surge days and times, and carefully cataloging the plates of vehicles going in and out. This database of plates gets near constant daily use, enabling rapid responders on foot and in cars to confirm known ICE vehicles in real time. ICE has begun swapping out cars and plates throughout the day to undermine this counter-surveillance, but the volume of submissions pouring in is only growing.

Whipple Watch describe their goals as threefold:

- to provide an early warning system about surges and convoys to the local rapid response networks,

- to gather data with a special focus on the license plate database, and

- to ensure that ICE knows they are being watched, even on their own turf.

Whipple Watch has undeniably succeeded in achieving these particular goals, even in the face of a hostile militarized force.

Much of ICE watch consists of patrollers in cars or on foot, monitoring and reporting on the movements of federal agents.

How It Works

Each chunk of the city (Southside, Uptown, Whittier, and so on) has rotating shifts of dispatchers, who admin a running Signal call throughout operational hours. Sometimes, multiple dispatchers overlap to split up the extra tasks of watching the chat, relaying reports to other channels, and checking license plates. Dispatch also helps people evenly distribute patrols across an area, takes notes, and assists people through confrontations. All patrollers in cars and on foot and stay on the call throughout their patrol. There is a constant flow of information, allowing other cars to decide whether they are well-positioned to join in, take over tailing the car, or continue searching for additional vehicles.

Since the structure has divided up into more granular neighborhood-based zones, people in many areas have also developed a daily chat system, with chats that are re-made and deleted each day to keep them clear and not maxed out of participants (as the maximum number of members of a Signal group is capped at 1000). Various areas of the cities and the suburbs have replicated the basic structure of this system but with slightly different models, chat structures, vetting systems, and data collection.

A data collection team collects anonymized data submitted from Whipple Watch and many of the local rapid response chats, aggregating them into consumable formats, such as interactive maps of hotspots. This team also admins the searchable database of license plates sorted by “confirmed ICE,” “suspected ICE,” “confirmed not ICE,” and other categories.

Additional place-based chats have emerged around school systems, faith communities, mutual aid grocery deliveries, and the like. Another development was the Neighborhood Networks intake chat, which acts as a clearinghouse for incoming volunteers. New people from anywhere in the city—or anywhere in the state of Minnesota—can be added and oriented to a list of chat options, and admins will add them to the open chats or connect them to the vetting and training processes for the more closed chats.

Most recently, dispatchers have experimented with a relay system in which patrollers who tail vehicles to the edge of their zone can communicate through dispatch across chats to pass off the vehicle to a patroller in the next region. This allows the patrollers to remain in tighter and tighter routes, which they can swiftly come to know intimately well in order to navigate them better than any ICE agents.

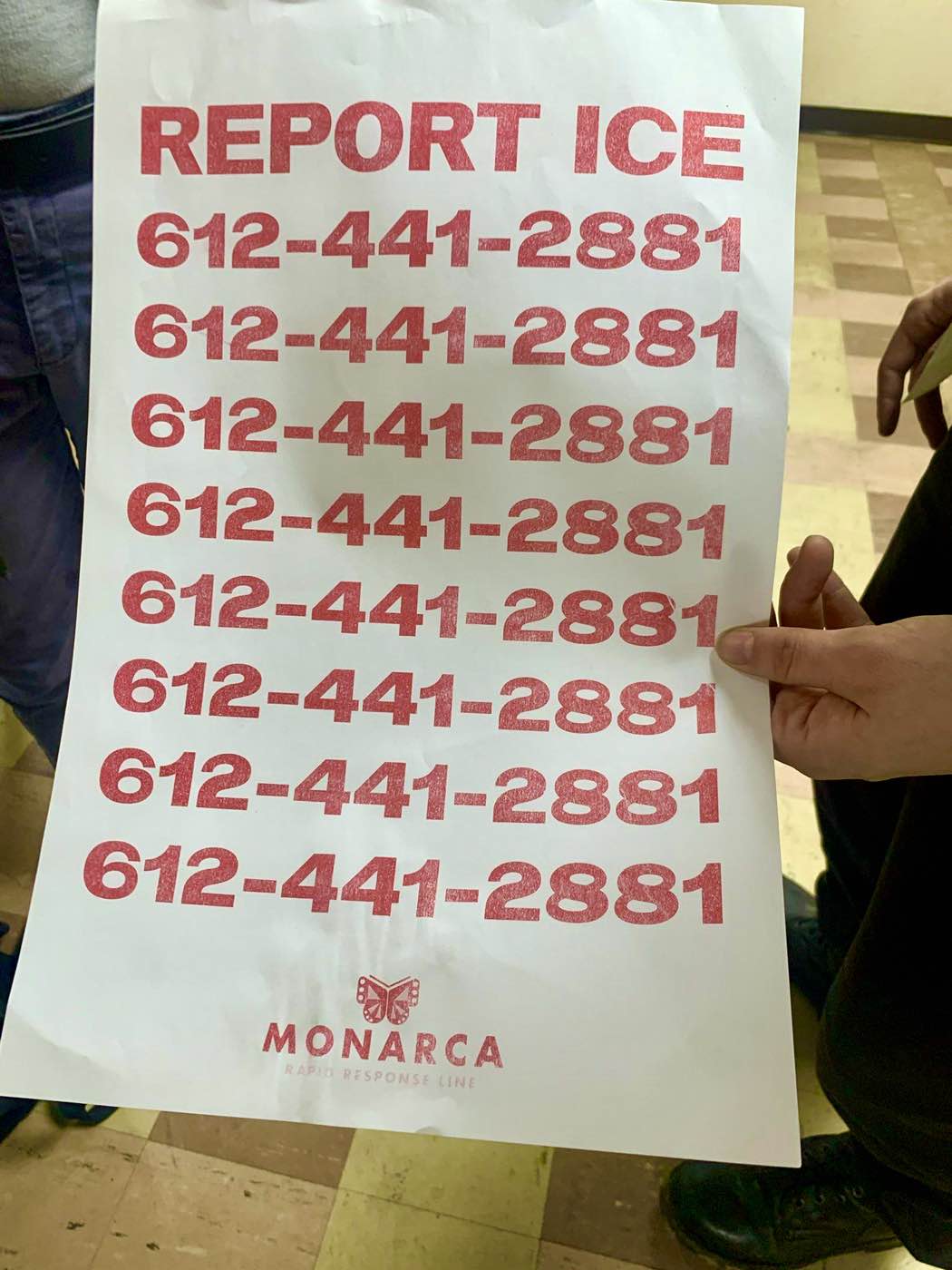

Finally, Spanish language relayers copy ICE alerts from dispatch calls and local chats, translate them, then send to large Spanish-language Signal and WhatsApp networks.

What might look from the outside like an over-formalization of chats for different kinds of information, or else like too little structure in the completely open calls that all patrollers for a given zone join in simultaneously, coheres into a highly effective, self-organized, and well-maintained communication ecosystem. Information moves reliably across scale through the chats and dispatchers, and patrollers quickly adopt cultural practices that enable them to avoid talking over each other and to relay information in a clear and organized manner. Volunteers self-select into shifts of varying lengths, deciding what routes to run based on their knowledge, skill, interest, and availability.

This system is constantly shifting, highly adaptable, somewhat difficult to explain to outsiders, and surprisingly easy to integrate into—once you get over the shock of receiving over 1500 new messages per day.

“You Don’t Know How Crazy It Is Here”

The response from ICE has been measurable. They have changed their tactics. They have been chased out of neighborhoods during operations. They have been caught discussing how scared they are and the fact that many of them have left.

They’ve also continuously and aggressively escalated their violence against observers. Patrollers who follow ICE too closely or for too long will often be boxed in so that between four and ten officers can surround the car, beat on the doors, yell, film, and threaten them with arrest. Patrollers who have blocked ICE with their cars have been rammed, have had their windows busted in, have been pulled out to be detained or arrested. People have been put into ICE vehicles, driven miles away, then thrown out of the car. Agents have taken people out of their cars, then driven their cars several blocks away and left them running in the street. Recently, agents have been pepper spraying cars—sometimes trying to fill the interior of the vehicle in order to force people out of it, other times just using the chemical weapon to brightly mark the cars for further harassment and targeting.

Recently, ICE agents threw a tear gas canister out of their vehicle while driving on the highway to try to deter someone from following them. Agents have not only followed patrollers home, but have identified the driver or vehicle following them and led drivers to their own home addresses as a form of intimidation. Patrollers shared with us that agents have beaten them, have tried to run them over, have driven directly at their vehicles head on, held them at gunpoint, shot out their tires, and dragged them out of moving vehicles. While the murder of Renee Nicole Good shocked the nation, it came as no surprise to those who have been on the streets of the Twin Cities over the past six weeks.

The Twin Cities Model: Don’t Copy It, Learn from It

What sets apart the Twin Cities rapid response network and its surrounding ecosystem is not strict adherence to a particular structure. It is a clear analysis of their conditions, a willingness to adapt, and the courage to fight back as the violence increases.

The people of the Twin Cities have paid close attention to their opponents. They know how ICE agents deploy, where ICE agents stage, how ICE agents dress, drive, and react. They live in a relatively small and densely populated urban area, walkable in many parts, gridded for easy navigation by car. People are connected to their neighbors, building on the connections that remain from past movements and uprisings. The mayor of Minneapolis is trying to maintain the liberal veneer of his administration; police are unlikely to deploy as reinforcements for ICE operations. These are concrete and observable conditions that have directly defined the design and implementation of resistance here.

Those embedded in the model are committed to agility and adaptability as conditions change. The city has neighborhoods with distinct demographics and characteristics, so the expansion of the model was built to vary from one neighborhood to the next. After the raids stopped, ICE deployed almost exclusively from one main location with limited entrances and exits, so organizers invested heavily in counter-surveillance there. When ICE operations switched to fast, random street abductions and door knocks, the only possible way to predict where they would act was to identify ICE vehicles as they approached, so people shifted focus to identifying ICE vehicles on the roads and staying on them. ICE needed to rely on surprise and ambush tactics, so responders employed noise—whistles and honking—to quickly give warning across distance. ICE officers don’t like to operate when outnumbered and don’t like to be surrounded, so patrollers amass cars and form impromptu traffic jam blockades.

Few of these conditions could have been predicted in advance. The only way to adapt effectively was to nurture an open, invitational culture that encourages taking initiative and welcomes self-organization.

We cannot overstate the importance of the courage pouring into the streets of the Twin Cities. It can be easy to write off rapid response networks, because we know that simply filming and observing this accelerating campaign of violence is not enough. Many networks across the country have demobilized themselves before they even got going by trying to rigidly control what their participants could do, despite widespread willingness to escalate. Trainers often preach non-interference; some rapid responders police each other in the streets for throwing projectiles or even for yelling. In some cases, this comes from a self-preservationist fear about repression targeting the NGOs involved in rapid response. In other cases, it shows up as a well-meaning but misguided focus on “safety” that is simply paternalism, deciding what risk levels are appropriate for other people.

Such overcautiousness can be found in the Twin Cities, too. There are trainers and dispatchers who, by default, tell people to disengage rather than supporting them in whatever they feel called to do. There are bystanders who get in the way of those who are taking action rather than in the way of ICE.

But the fight here is defined by those who push the envelope. People use their cars and bodies to block agents and de-arrest targeted people. They throw snowballs and rocks; they kick back canisters of tear gas. They cover cars and agents with paint and break the windows of their cars. They don’t stop screaming in the faces of abductors when they are hit, pepper sprayed, or shot with rubber bullets. They are witnessing the masked abductions, undisclosed disappearances, and record-breaking deaths of this new emboldened ICE, and they are willing to take real risks to stop them. They are experiencing the retaliative violence, and they are more, stronger, and braver in spite of it.

Being ready for the incoming surge of ICE enforcement in your city—and mark these words, it is coming—means studying the terrain you are fighting on and getting creative. What works best for your city likely won’t look exactly like these daily observation units at their headquarters and mobile patrols of rapid responders. It will require a thorough analysis of how best to use your strengths and exploit their weaknesses in your specific circumstances. Start studying, planning, connecting, and experimenting now.

We look to the Twin Cities, not to replicate the details, but for their clarity of analysis, swift and decisive action, agile experimentation, deep care for each other, and infectious courage.

This report was submitted by visitors to the Twin Cities, who were kindly welcomed into the network for a few short days. Thank you to all those who showed us your city, talked us through the systems, and brought us along on patrols. Love and rage.

Resources

- Eight Things You Can Do to Stop ICE

- Seven Steps to Stop ICE

- When the Feds Come to Your City: Standing Up to ICE—A Guide from Chicago Organizers

Further Reading

- The Noise Demonstrations Keeping ICE Agents Awake at Their Hotels: A Model from the Twin Cities

- Minneapolis Responds to the Murder of Alex Pretti: An Eyewitness Account

- Protesters Blockade ICE Headquarters in Fort Snelling, Minnesota: Report from an Action during the General Strike in the Twin Cities

- From Rapid Response to Revolutionary Social Change: The Potential of the Rapid Response Networks

- Rapid Response Networks in the Twin Cities: A Guide to an Updated Model

- North Minneapolis Chases Out ICE: A Firsthand Account of the Response to Another ICE Shooting

- Minneapolis Responds to ICE Committing Murder: An Account from the Streets

- Protesters Clash with ICE Agents Again in the Twin Cities: A Firsthand Report

- Minneapolis to Feds: “Get the Fuck Out”: How People in the Twin Cities Responded to a Federal Raid